Christmas with Charlie

by Lisa Stein Haven

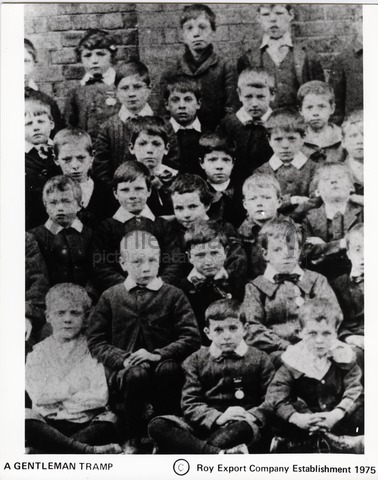

“How well I remember one Christmas Day sitting on that same seat at Hanwell school, weeping copious tears. The day before I had committed some breach of rules. As we came into the dining-room for Christmas dinner we were to be given two oranges and a bag of sweets. . .

I am speculating what I shall do with mine. I shall save the peel and the sweets I shall eat one a day. Each child is presented with his treasure as he enters the dining-room. At last it is my turn. But the man puts me aside.

‘Oh, no—you’ll go without for what you did yesterday.’”

–Charlie Chaplin: “A Comedian Sees the World” (1933-4)

If you know anything about Charlie Chaplin, you may have heard this particular story. And if you know this particular story, you know that many report that Christmas for him often seemed to be colored by this particular childhood event. Or was it? Christmas with Charlie, as it is passed down to us through the recollections of others, is nothing if not full of contradictions. Even in the essay cited above, “A Comedian Sees the World,” Charlie tells us about this sad Christmas memory, but then hints in another passage of at least knowing about, or recognizing, the same warm Christmas feelings and impulses we all do. While in London, he writes: “As I walk around West Square, I come upon a stationer’s shop where they sell toys, sweets and tobacco. The store has an odor that awakens memories. It smells Christmassy. In the window I see a Noah’s ark with painted wooden animals. I can’t resist it. I go in and buy it just to get a whiff of the paint and the feel of the excelsior that’s packed inside.”

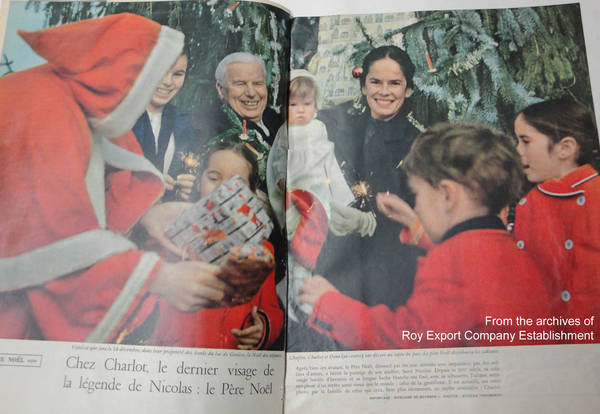

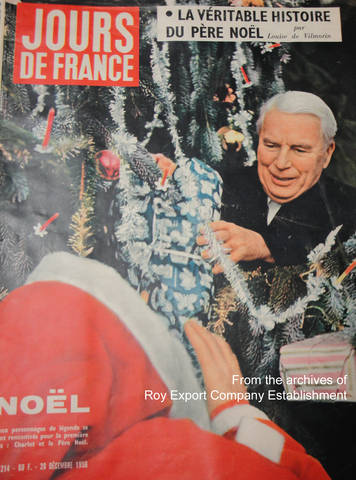

In a similar spirit, Charlie Chaplin, Jr. gives a long and loving account of his experience in 1936 celebrating “Christmas on the hill”—in the Summit Drive house in Beverly Hills. “Christmases at my father’s home,” he writes, “form a composite picture in my mind, for every one of them was almost identical in style and texture. Even the weather was the same. As far back as I can remember, the Christmas days of my boyhood were sunshiny and mild.” In his account we read of the gathering of a tight-knit group of friends and relatives, including Uncles Sydney and Wheeler and their families, Alf and Amy Reeves, Constance Collier, King Vidor, Tim Durant, Dr. Reynolds and, of course, Douglas Fairbanks for a brunch that always included at least roast beef and Yorkshire pudding somewhere on the menu. Frank and the other servants could always expect generous bonuses and despite his Hanwell memories, his father always rewarded the boys with many “lavish” and thoughtful presents. One such thoughtful present was a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat minor for piano and orchestra. As Charlie Jr. recalls, “one night at Dad’s house I had tuned the radio in on that concerto and, unable to tear myself away, had fallen asleep listening to it. Dad and Paulette had remembered and bought me the album.”

Perhaps one of the most unusual Chaplin Christmas tales is told, however, by Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel. The scene is Hollywood, 1930, a Christmas party at the home of Spanish comedian Tono and his wife. The guests are a group of Spanish actors and screenwriters plus Charlie and Georgia Hale. Buñuel relates that they all decorated the Christmas tree with the gifts they had brought for that purpose. Then the entertainment began and Buñuel was soon put off by the recitation of an overly patriotic Spanish poem. So, he enlisted the help of two other guests. “When I blow my nose,” he whispered, “that’s the signal to get up. Just follow me and we’ll take that ridiculous tree to pieces!” However, they found it a difficult task to dismember the tree and so focused on destroying the presents instead. As Buñuel recalls, “the room was absolutely silent; everyone stared at us, openmouthed.” Still, just a week later, Charlie invited the group to his house for New Year’s Eve where they found another Christmas tree loaded with presents. He greeted Buñuel only with the following remark: “Since you’re so fond of tearing up trees, Buñuel, why don’t you get it over with now, so we won’t be disturbed during dinner?”

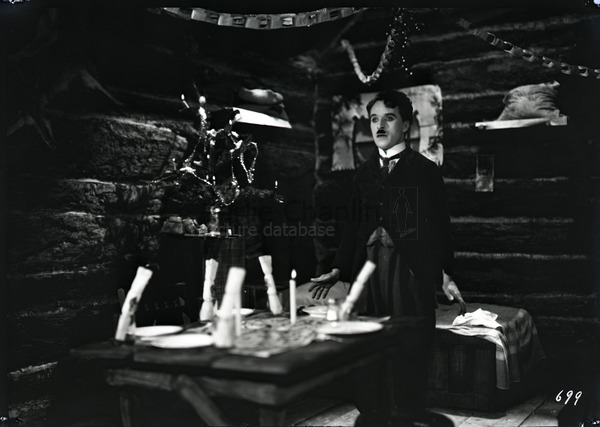

So, if these anecdotes are any indication, Christmas with Charlie must have been very much like our own—filled with family and friends and an occasional oddball event. But since he died on Christmas in 1977, it’s also a good day to honor his memory—maybe by watching that great holiday classic, The Gold Rush.

Sources:

Buñuel, Luis. My Last Sigh. Trans. Abigail Israel. NY: Knopf, 1983.

Chaplin, Charles. “A Comedian Sees the World.” Women’s Home Companion. Sept. 1933: 7-10, 80, 86-9; Oct. 1933: 15-17, 102, 104, 106, 108; Nov. 1933: 15-17, 100, 102, 104, 113, 115, 116, 119; Dec. 1933: 21-23, 36, 38, 42, 44; Jan. 1934: 21-23, 86.

Chaplin, Charles, Jr. My Father, Charlie Chaplin. NY: Random House, 1960.