Call for Papers: Charlie Chaplin in the Eye of the Avant-Garde

Call for papers - Conference

Charlie Chaplin in the Eye of the Avant-Garde

Nantes, December 5th and 6th, 2019

Musée d’arts de Nantes

Institut ACTE (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne)

Venue: Auditorium, Musée d’arts de Nantes

Conference Directors: Claire Lebossé, José Moure

Advisory Board: Martin Barnier (Université Lyon 2), Francis Bordat (Université Paris-Nanterre), Élodie Evezard (Musée d’Art de Nantes), Kate Guyonvarch (Chaplin office, and Roy Export SAS), Morgane Jourdren (Université Angers), Claire Lebossé (Musée d’arts de Nantes), Sophie Lévy (Musée d’arts de Nantes), José Moure (Université Paris 1)

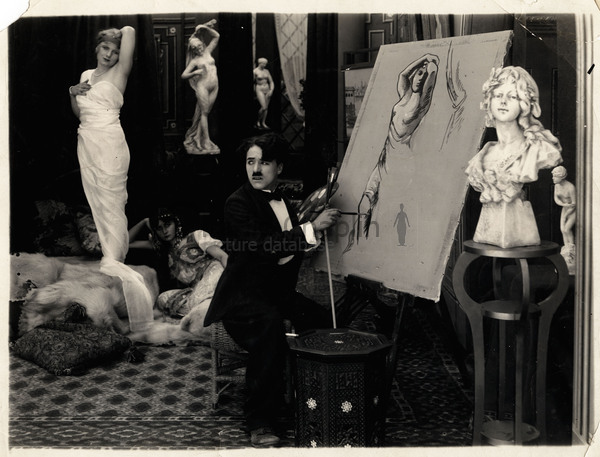

From 18 October 2019 to 3 February 2020, the Musée d’arts de Nantes is organising an exhibition entitled Charlie Chaplin in the Eye of the Avant-Garde highlighting for the first time the connections between the cinematic work of Charlie Chaplin and avant-garde experiments in the visual arts. As the first international star in the history of cinema, Charlie Chaplin has exerted a powerful fascination ever since the invention of his Tramp persona in 1914. However, the interaction between the work of Chaplin and the artistic output of his contemporaries remains unexplored. Charlie Chaplin in the Eye of the Avant-Garde, which brings together many different art forms (paintings, photographs, drawings, sculptures, documents and, of course, flm), offers an immersion in the visual world of the first half of the 20th century, with works by Frantisek Kupka, Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim, John Heartfeld, and Claude Cahun…

The conference will be based on the same four axes as the exhibition:

Machine Man

The geometrical way that Chaplin’s tramp moves, with his jumpy walk and his famous 90 degree turn, inspired Fernand Leger in his development of a cubist Chaplin. It also evokes machine movements which Chaplin either mimes (c.f. his transformation into a clockwork statue to escape capture in The Circus) or becomes part of (when Charlie is swallowed by the conveyor belt and ends up trapped the cogs, in Modern Times.) Contemporary admirers of Chaplin such as Frantisek Kupka and Francis Picabia were similarly preoccupied by a fascination for machine movements and the art of engineering heralding a new world order.

The poetry of the world

The freedom of the Tramp is exemplified in his refusal to consider the world as a constraint to which he must submit: demonstrated in his reinterpretation of objects. Objects are diverted from their intended functions and lose all practicality, such as the scene in The Pawnshop when Chaplin takes the alarm clock apart and ends up completely destroying it. Objects undergo poetic transformation in the hands of an inventive hero trying to make the world fit his needs (the bread roll dance in The Gold Rush, 1925) in the same way as in the works of Victor Brauner et François Kollar. The counter-uses of objects proposed by Chaplin can be seen as deviations of meaning based on semantic ambiguities, establishing close, formal links with the work of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray.

Spectacle « mis en abyme » The travelling world of performers is a privileged universe for the tramp character, himself a wanderer, on the outskirts of society (The Circus, 1928 ; Limelight, 1952). Chaplin loved the microcosm of the circus, as did Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall or Alexander Calder. There, reality is transformed, reflected by deforming mirrors- mockery and doubt question the ordinary. The clown and the tightrope walker are often used as metaphorical representations of artists, deliberately putting themselves in danger for the audience or on the high wire. In his work Chaplin equally explores the joyous burlesque of the tramp and the melancholy of the ageing white clown (Limelight) This exploration of the artist figure is to be accompanied by a reflection on the film industry in which he evolved.

The absurdity of history

The success of the tramp character places an emblematic and displaced character at the centre of Chaplin’s film work. The poverty of one category of the population is forced upon the eyes of the viewers, and in particular upon the eyes of the cameras of Lewis Hine, Walker Evans and Berenice Abbott. The theme is all the closer to Chaplin in that he experienced extreme poverty in his childhood (The Kid, 1921). His work also expresses clear antimilitarism, from Shoulder Arms (1918, echoing the work of artists who experienced the trenches during the First World War and often attended screenings of Chaplin films when on leave) to The Great Dictator (1940), ridiculing Hitler and Mussolini through infantilization and derision, similar to photomontages by John Heartfeld, himself a Chaplin admirer.

Submissions

Please send an abstract (1000 to 2000 characters) in English or French, a short curriculum vitae, a bibliography of maximum 5 lines, and your contact information to:

José Moure (jmoure@univ-paris1.fr) and

Claire Lebossé (colloquemuseedartsnantes@gmail.com).

Deadline for submissions (extended): May 22nd 2019

Answers will be given in June.