Collecting Charlie Chaplin

An article by Lisa Stein Haven

In the press book for Modern Times, United Artists wrote in “Chaplin the Collector” that Charlie Chaplin “has been offered huge sums for his Napoleonic Saxony porcelains.” He collected autographed first editions of Frank Harris’s novels, and “a complete, beautifully bound set of Punch dating from its first issue.” Chaplin’s extensive library also included such rare items as a miniature set of The Complete Works of Shakespeare (1905) that one rare bookseller today quotes in his ad for a similar set, “Bondy recalled having seen only one complete set during his many years in miniature books, that was in the collection of Charlie Chaplin.” It is also well known that Charlie collected the autographs of all the great and noble people that he met over the years, a caricature of which can be seen in his cameo appearance in Marion Davies’ 1928 silent film Show People. In other words, if a person is to take his behavior as our model, he or she can quickly decide that collecting is a respectable and worthwhile venture and was so, even for those who are “collectible” today.

If a person decides to “collect Charlie Chaplin,” the task seems fairly easy. Look for anything and everything with his name on it, associated with it, or juxtaposed to it in some manner. This is the easy way out, and, while rewarding—because there are endless such items out there to be had—I want to propose what I think is a more creative option. I will call this “context” collecting for lack of a better term. Context collecting, as I would define it, is simply collecting around Chaplin in history through material culture. Chaplin used to say, “If you want to know me, watch my movies.” Unfortunately, there are only 81 of those. In this material society, humans hunger for more and more and more, especially in the area of information. Why not then collect some of that material and see what information it provides?

The ideas for context collecting Charlie Chaplin are endless. I have presented below some ideas for context collections with examples from each. Context collecting is infinite; there is no rigid beginning or ending.

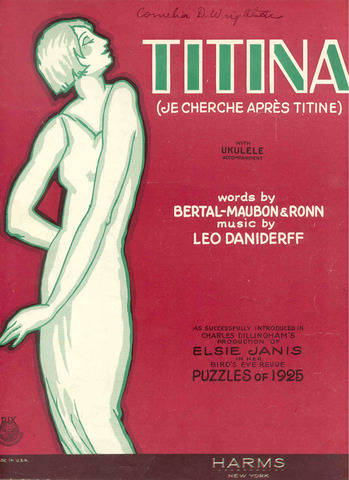

Sheet Music

Everyone knows that Charlie was a prolific composer and it is easy to find examples of his work in the form of sheet music. More difficult, and perhaps more interesting, is collecting the music that inspired his movies or that is associated with him in some other way. In My Autobiography (MA), Charlie lets us know that “Too Much Mustard” (Tres Moutarde) set the mood for his Keystone film Twenty Minutes of Love, that “Mrs. Grundy” (and this one is hard to track down) inspired The Immigrant ; “the tune had a wistful tenderness that suggested two lonely derelicts getting married on a doleful, rainy day” (225). Likewise, The Gold Rush was inspired by “Auld Lang Syne,” and City Lights by “La Violetera”—a song introduced to him coincidentally by Raquel Meller whose American career Charlie tried to promote in 1928 (“The genius of Raquel Meller is something more than a native gift. Her work shows an intellectual control and a refinement of feeling unexcelled by any other artist I have ever seen.”—Chaplin in press release) and who had earlier been famous for this song in 1923 and is, in fact, pictured on the cover of one version of its sheet music. David Robinson tells us in Chaplin: His Life and Art that “And They Called It Dixieland” was played on the set during the filming of The Count (174). Other important songs are easy to figure out from the movies themselves: “Je Cherche Aprés Titine” from Modern Times is just one example. If this list feels too confining, the collector can reach back further in Chaplin’s career and find “The Honeysuckle and the Bee,” supposedly the first piece of music that awakened the young man’s senses to the beauty of music or “Jack Jones,” the first piece he is to have sung onstage as a lad of five (MA 10-11). Further afield are pieces that others equate with Charlie experiences. Helen Hayes in her autobiography A Life in Three Acts claims that Irving Berlin’s song “Remember” takes her back to a specific night in her life in New York City when Charlie arrived too late for a particular Greenwich Village party to which he had been invited and suggested they all go over to Irving’s house for a while. Hearing the song “Remember” brings back for her the image of that night when Charlie and Irving sat at the piano in Irving’s apartment and played the tune over and over throughout the wee hours of the morning. What images might the hearing of this song then bring to us?

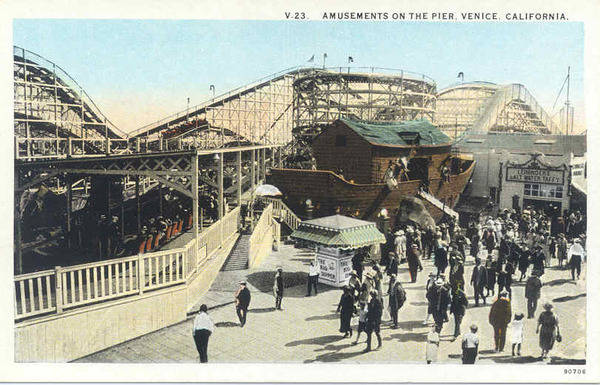

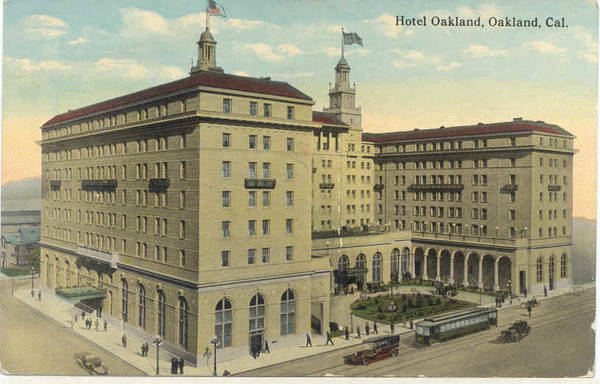

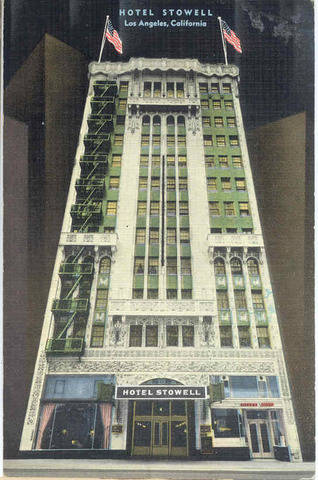

Postcards

Collecting postcards is by far the most economical means of context collecting and it can take endless forms. Collecting postcards of Charlie’s friends, colleagues, girlfriends, wives, leading ladies, or family members probably comes to mind first and is the easiest. What about something more imaginative? While it is not important to collect postcards contemporary to the time period in question, it makes it more interesting. Consider, then, the following categories: movie sites, oft-frequented places—especially those mentioned in MA, hotels and restaurants—both in California and New York, the 1918 Bond Tour, and the European tours (especially 1921 and 1931-32), and theatres included on the Sullivan and Considine circuit that Charlie would have played in with Karno. This list is by no means exhaustive and each category requires a bit of research. The best part about this type of collecting is that the collector him/herself decides what is worth including in the collection. If it is not of interest or fails to provide the type of knowledge about Chaplin that is of personal importance, simply don’t include it.

Consider the Hotel Stowell in downtown Los Angeles. Chaplin misspells it in MA (Stoll) but describes it as his place of residence upon returning to Los Angeles for good for his seventh Essanay film—“a middle-rate place but new and comfortable” (183). It was here that he had an argument on the phone with Anderson regarding a proposed appearance at the New York Hippodrome for $25,000: “My bedroom window opened out on the well of the hotel, so that the voice of anyone talking resounded through the rooms. The telephone connection was bad,–‘I don’t intend to pass up twenty-five thousand dollars for two weeks’ work!’ I had to shout several times. A window opened above and a voice shouted back: ‘Cut out that bull and go to sleep, you big dope!’

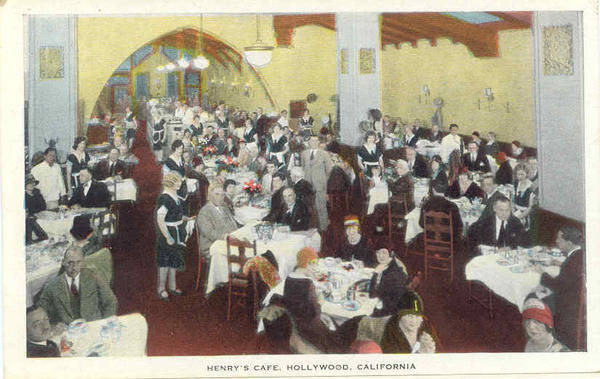

Henry’s Delicatessen was located on Hollywood Boulevard in California and was Henry Bergman’s venture into the world of professional food service as financed by Chaplin. It opened in the late 1920’s and closed a few years later, even though it was a great success—and the only restaurant of its kind while it was open. A postcard exists of Henry’s, called here Henry’s Café and, being an interior view, shows Mr. Bergman himself seated at a table right in the center of things. As Charlie was a frequent patron, one can’t help looking at each and every other face in the place to see if one of them is his.

Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles is the location for the moment in The Kid in which the truck with Jackie and Charlie in it finally stops and the driver runs off in fear. The clear real photo postcard shows the building visible in the background of that poignant scene and it is made more interesting because it is a postcard from the 1920s.

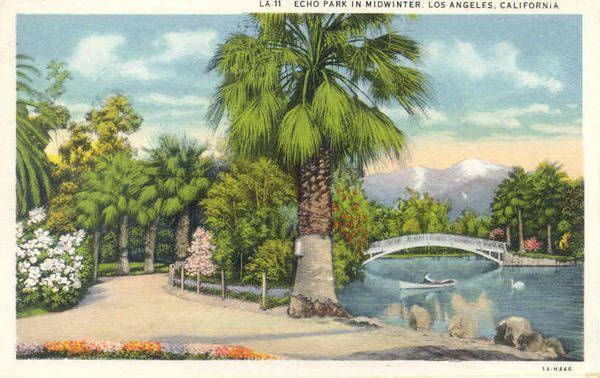

Echo Park is a well-known location for many of the Keystone films such as Mabel’s Married Life. Upwards of fifteen different views of the park exist, many with the famous bridge or snack stand seen in this particular film as the center of focus.

The park just across Sunset Boulevard from the Beverly Hills Hotel in California is the location for the park scene just before the tramp enters the fancy dress party in The Idle Class. This postcard is taken from exactly the same spot at which the tramp and another gentleman sit on a bench and the tramp is mistaken for a pickpocket.

At the Hotel Adlon in Berlin, Germany where Chaplin wanted to stay in 1921 but wasn’t able until 1931, the following event occurred, as related in the book Hotel Adlon: The Life and Death of a Great Hotel : “The news of Chaplin’s coming had been spread abroad, and the pavement on Unter den Linden was covered by a dense mass of people through which he had to fight his way from the car to the hotel doors, shaking hands, signing albums, returning smiles and greetings and struggling frantically not to be trodden underfoot. His navigation light, as he was washed to and fro on the bosom of this human tide, was the pale-blue peaked cap of the Adlon porter, who finally managed to rescue him and thrust him to safety through the revolving door. But then, when it seemed that all was well, he suddenly stopped in the middle of the reception hall and gazed at himself in comical bewilderment. His trousers were coming down! Souvenir-hunting admirers had robbed him of every button. He could do nothing but clutch them and make hastily for the lift, using that shuffling gait that all the world knows” (193). Interestingly, a line to the effect that the Adlon boasts “the lobby in which Chaplin dropped his trousers” is still used in Hotel Adlon publicity.

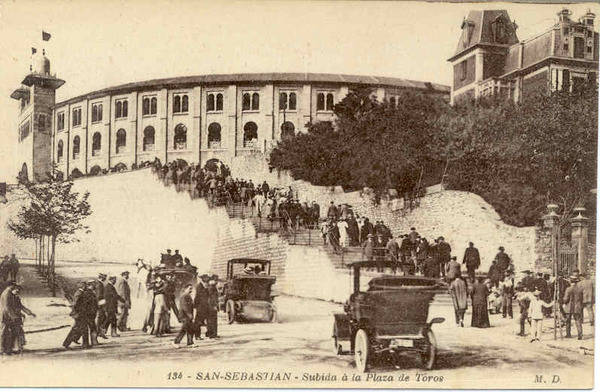

On another leg of the 1931 European tour (no pun intended), Chaplin tells of his adventure in San Sebastian, Spain at the bullfights in “A Comedian Sees the World,” “A most beautiful yet revolting afternoon was spent at a bull fight in San Sebastian…My friend, the Marquis de Sorreana, warned me that I would probably have several bulls dedicated to me, so I ordered four cigarette cases for the event….That afternoon I saw a dramatic killing. Imagine a large arena, the silence of thirty thousand people and standing in the bleak sunshine a man and a bull facing each other, the bull in the throes of death.”

Miscellaneous Ephemera

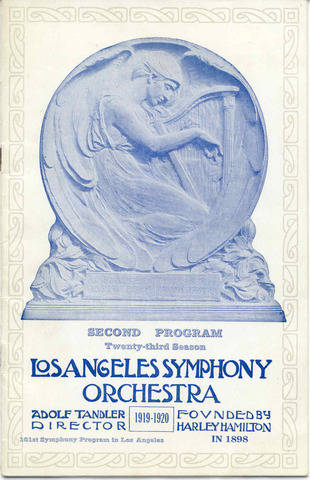

Outside of these two types of material, the options are endless. One might want to collect playbills from New York during periods when Charlie was in the city, menus from restaurants contemporary with times he might have frequented them, tourbooks and guides from places he visited on his frequent travels, or symphony programs—especially from the LA area. Charlie loved hearing the symphony and even Lita mentions occasions of their attendance at the Hollywood Bowl in her book My Life with Chaplin. What may not be known and what I only discovered from my context collecting is that Charlie was a supporting patron of the symphony when it was still housed at The Auditorium in downtown LA. He relates in MA only that “occasionally, a symphony at Clune’s Philharmonic Auditorium” (200) was on his list of “routine pleasures” as early as 1916. Upon my discovery of a Los Angeles Symphony Program from 1919, I found listed inside “Mr. And Mrs. Charles Spencer Chaplin” as such patrons. Interestingly, no other movie personalities were listed.

Walter Benjamin, a literary critic of the Frankfurt School that was active during the Weimar period in Germany, wrote in his essay, “Unpacking My Library,” “The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are frozen as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a true collector, the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object”(487). Therefore, in “collecting Charlie Chaplin” in this manner, the collector can open his or her “magic encyclopedia” of things and discover parts of Charlie Chaplin not written down in any book.

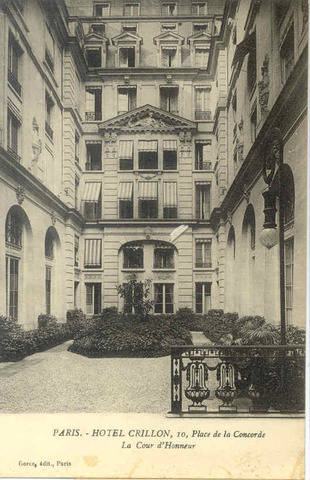

Can you identify the Chaplin connections to the following places found in these postcards?