Chaplin - A Musical Biography

“Chaplin’s musical genius is that of organized revolt against conventions, combined with perfect feeling for the real thing.” - Ray Rasch

Charles Chaplin recalled that in his childhood his mother would take him to the theatre, where he would stand in the wings listening to her and the other acts of the music hall shows. At home, in the happier times, she would entertain him and his step-brother by singing, dancing, reciting and imitating other artists. His own very first appearance on the stage at the age of five was precipitated when her voice broke in front of a particularly tough crowd. Charlie, already a natural performer, it seems, was pushed on in her stead and sang two songs, pausing only to pick up coins thrown by the surprised and amused audience.

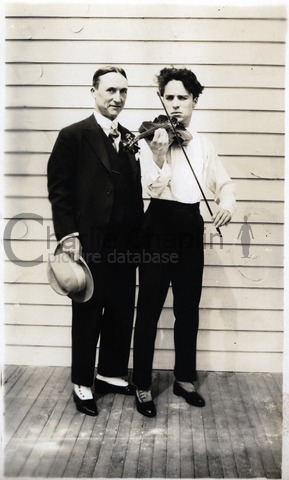

In 1898, aged 9, he began his own music hall career with a troupe of juvenile clog dancers, the Eight Lancashire Lads. He was to remain in the theatre, alternating work and periods of unemployment, until he joined Fred Karno’s company. As a rising star with Karno he went to America in 1910 to tour the vaudeville circuits. Stan Laurel, a fellow Karno performer, recalled that during their 1912 US tour Charlie “carried his violin wherever he could. Had the strings reversed so he could play left handed, and he would practise for hours. He bought a ‘cello once and used to carry it around with him. At these times he would always dress like a musician, a long fawn coloured overcoat with green velvet cuffs and collar and a slouch hat. And he’d let his hair grow long at the back. We never knew what he was going to do next.” Chaplin later wrote that “each week I took lessons from the theatre conductor or from someone he recommended. I had great ambitions to be a concert artist, or, failing that, to use [my violin] in a vaudeville act, but as time went on I realised that I could never achieve excellence, so I gave it up.”

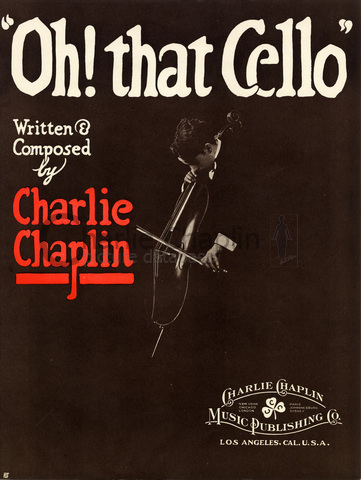

At the end of 1913 Chaplin left Karno to remain in America and work in moving pictures. While working at the Mutual Film Company he had the opportunity to meet musicians such as Paderewski and Leopold Godowsky who visited the now famous movie star. In 1916 he set up his own music publishing company. “We printed two thousand copies of two very bad songs and musical compositions of mine – then we waited for customers. The enterprise was collegiate and quite mad. I think we sold three copies, two to pedestrians who happened to pass our office on their way downstairs.” In fact the Charles Chaplin Music Company closed shop after publishing three Chaplin songs: Oh! That Cello, There’s Always One You Can’t Forget, and The Peace Patrol.

Film was obviously Chaplin’s most important concern, and in 1918 he moved into his own studios and could exert total production control.

In the silent period it was usual to commission professional arrangers to devise suitable musical accompaniments for major films. These were generally compiled from published music, and performed live by whatever instrumental combinations each individual cinema could afford. Chaplin always had an interest in the music for his feature films. He approved and co-compiled scores for A Woman of Paris (1923) with Fredrick Stahlberg, and with Karli Elinor for The Gold Rush (1925). However not until City Lights did he complete a full-length score – a début heard by millions around the world when the film was released.

According to conductor-composer (and Chaplin music expert) Timothy Brock, Chaplin was a born tunesmith with real composing talent. “Even if he could neither read nor write music, complex, sophisticated compositions were complete in his head. His only problem was to get his collaborators to understand and transpose onto paper what he could hum or sketch out for them on the piano.” Chaplin remembered the only happy thing in his view about the arrival of the talkies as being “that I could control the music, so I composed my own. I tried to compose elegant and romantic music to frame my comedies in contrast to the tramp character, for elegant music gave my comedies an emotional dimension. Musical arrangers rarely understood this. They wanted the music to be funny. But I would explain that I wanted no competition, I wanted the music to be a counterpoint of grave and charm, to express sentiment ….”

As Brock explains: “For his scores, Chaplin was aided by what he termed as a ‘musical associate.’ This was a person who, to varying degrees of participation, helped with the notation and orchestration of his compositions. Chaplin played both the violin and piano by ear, but, like many of the great popular composers of any era, was unable to transcribe the notes on paper. Yet however constrained in his ability to notate his work, nearly every score has the indelible Chaplin mark. No matter who the associate, the musical structure and approach remains distinctively his own. Furthermore, the soundtrack recordings contain extremely specific stylistic choices unique to Chaplin. For example, as a violinist himself, he required the string player to mimic his style of playing and his unambiguous traits are ever-present in the extended violin solos in each of his scores. The majority of the extended violin solos (and every Chaplin film score has them) are written in a beautifully odd, yet specific, manner. His string writing in general contains a unique set of principles revealing that he was a composer bent on sound, and not technical affability.”

After City Lights, Chaplin composed the scores for all of his films. As Brock remarks, “His writing was so moment-specific, so tightly synchronized, that one can nearly follow a Chaplin film by only hearing its score without the benefit of the image.”

The Gold Rush, originally released in 1925 as a silent film, was re-released in 1942 with a narration by Chaplin and a musical score that he composed. The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux followed. Later he took obvious pleasure in creating the pastiches of Edwardian music hall songs and acts for Limelight (1952), and later writing parodies of 50s pop songs for A King in New York (1957). His interest in pastiche and parody is not limited to the music, as the lyrics too are full of humour and word-play.

The Chaplin family left Hollywood in 1952. In his home in Switzerland Chaplin continued to develop his love and knowledge of music and to entertain musicians, among them Arthur Rubinstein, Isaac Stern, Rudolf Serkin, and Clara Haskil. His daughter Josephine has nostalgic memories of how, regularly after supper, he would insist that the lights were turned off, and that the family listen by candle-light to record after record of classical music.

The Chaplin family archives hold many audio tapes of Chaplin working on the piano, improvising and humming as he composed. He once said that even if he did not remember how a tune went, he could remember the pattern it made on the black and white notes of the keyboard. Between 1958 and the early 1970s he composed and recorded music for all his other silent 1918-1928 films: Shoulder Arms, The Pilgrim and A Dog’s Life (re-released together as The Chaplin Revue), The Circus, The Kid, The Idle Class, Pay Day, A Day’s Pleasure, Sunnyside and A Woman of Paris. Many of his tunes were hits, in particular those from A Countess from Hong Kong sung by Petula Clark in the late 1960s. Smile from Modern Times has been recorded by hundreds of artists, from Nat King Cole to Michael Jackson.

“To work is to live - and I love to live,” Chaplin, aged 87, told journalists on June 30, 1976. He died a year and a half later on Christmas day 1977. The music he composed until nearly the end of his life is a testament to his love for work, and for life.