Chaplin at Keystone: The Tramp is Born

By Jeffrey Vance, adapted from his book Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema (New York, 2003) © 2009 Roy Export SAS

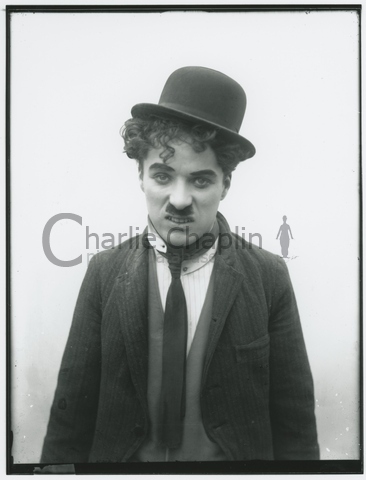

Building on traditions forged in the commedia dell’arte which he learned in the British music halls, Charles Chaplin brought traditional theatrical forms into an emerging medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. The birth of modern screen comedy occurred when Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and stepped into his impossibly large shoes for the first time at the Keystone Film Company. The comedies Chaplin made for Keystone chart his rapid evolution from music hall sketch comedy artiste to master film comedian and director.

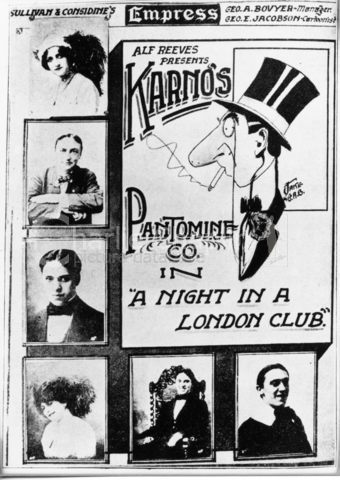

It would be easy to mistake the story of how Chaplin stumbled into his first motion-picture contract as the plot of a Chaplin comedy, were it not true. Alfred Reeves, manager of the Fred Karno theatrical company touring in America, received a telegram at the Nixon Theatre in Philadelphia on May 12, 1913, which read, “IS THERE A MAN NAMED CHAFFIN IN YOUR COMPANY OR SOMETHING LIKE THAT STOP IF SO WILL HE COMMUNICATE WITH KESSEL AND BAUMANN 24 LONGACRE BUILDING BROADWAY.” (1)

Reeves, believing the telegram must be referring to Chaplin, showed it to him. When Chaplin discovered that the tenants of the Longacre Building were mostly attorneys, he imagined that his great-aunt, Elizabeth Wiggins, had died and left him an inheritance. He immediately arranged a day trip to New York City.

Chaplin was disappointed to discover that the telegram had been sent by Adam Kessel Jr. and Charles O. Baumann, owners of the New York Motion Picture Company, who wanted to sign him as a comedian with the Keystone Film Company. Keystone’s lead comedy player, Ford Sterling, was intending to leave to start his own company, and they needed a replacement. An official of the New York Motion Picture Company and Mack Sennett, who ran Keystone, had both seen Chaplin in one of his tours and recognized his potential for film comedy. Chaplin was lured to accept the Keystone offer by the large salary: $150 weekly for three months raised to $175 weekly for the rest of the year; which was more than double his Karno salary of $75 a week. In September 1913 he signed his first film contract for a period of one year with the Keystone Film Company, beginning December 13, 1913. (2)

Chaplin had considered appearing in motion pictures before he received the offer from Keystone, wanting to purchase the motion-picture rights to all of Fred Karno’s sketches and make films of them. Ironically, Chaplin actually believed that making movies would help his stage career. He had seen some Keystone films and was not particularly impressed. “I was not terribly enthusiastic about the Keystone type of comedy, but I realized their publicity value. A year at that racket and I could return to vaudeville an international star,” he had surmised. (3)

Motion-picture comedy began with a simple comic situation, in the Lumiére Brothers’ L’Arroseur arrosé (Watering the Gardener, 1895) in which a boy steps on a garden hose as a gardener waters a lawn, cutting off the water, only to step off just as the gardener peers quizzically at the nozzle and is doused with the restored flow of water. Soon the chase developed as the essential element of comedy. In Europe, Pathé Frères, the great French film company, made trick and chase films. America lagged behind Europe in the development of film comedy, and Chaplin was not the first comic star of the cinema. Foremost of the Europeans was Max Linder of France, a gifted artist who had been making films since 1905 for Pathé, and cinema’s first international comedy star. His style and technique influenced Chaplin. Linder’s character was a resourceful and gallant boulevardier who ingeniously managed to extricate himself from the many predicaments that confronted him. Other star comedians, such as Polidor and Rigadin (Charles Prince), were popular as well prior to World War I when continental Europe rather than American production dominated even American screens. Chaplin was not even the first comic film star in America. That distinction goes to the fat and genial John Bunny, who had made a successful series of comedy films from 1910 to 1915 for the Vitagraph Company. However, from its inception, Keystone consistently produced the best American comedies of early silent film.

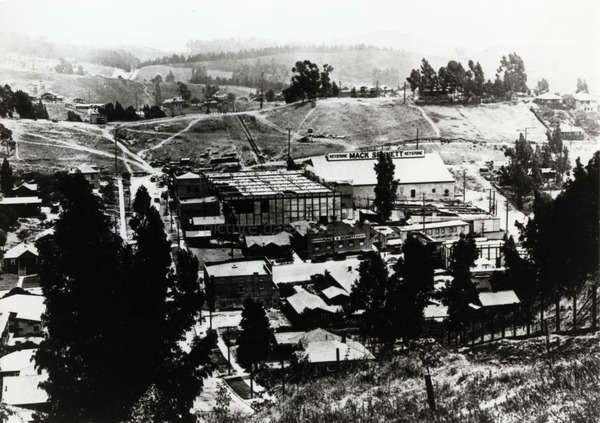

The Keystone Film Company was presided over by Mack Sennett, frequently billed in his lifetime as “the king of comedy.” Irish Canadian-born Sennett worked as a boilermaker before failing as an actor in burlesque and musical comedy. He joined the American Biograph Company in New York City in 1908 as an actor and there learned film craft from the leading American film director, D.W. Griffith. By late 1910 Sennett was scenarist and director of many of Biograph’s comic productions. Two years later, Kessel and Baumann hired Sennett as production chief of their new comedy studio in California, the Keystone Film Company.

Keystone was based in the former Bison Studios at 1712 Alessandro Street (now Glendale Boulevard), in the Edendale district of Los Angeles, near present-day Echo Park. Relocating to the West Coast, Sennett brought his principal players from Biograph to Keystone: Mabel Normand (with whom Sennett had a long and tense intimate relationship), Fred Mace, and Ford Sterling. The original Keystone players were quickly augmented by Roscoe Arbuckle (known as “Fatty“), Chester Conklin (known as “Walrus”), Mack Swain (called “Ambrose”), and others. At the time Chaplin joined Keystone, the company was producing twelve one-reel comedies plus one two-reel comedy a month. Sennett directed the first unit while Henry “Pathé” Lehrman—a former streetcar conductor whose nickname derived from his fraudulent representation of himself to D. W. Griffith as associated with Pathé Frères—directed the second unit.

Sennett possessed an intuitive, almost uncanny understanding of film comedy. He was the creative force behind the Keystone Cops (a madcap mockery of the police force), the Sennett Bathing Beauties, and custard-pie fights in motion pictures. In Sennett’s films, frantic pacing of broad slapstick comedy took precedence over characterization and story.

Although crude and obvious, these comedies also were simple and joyous affairs, brimming with ebullience and vitality. Keystone rarely deviated from certain types of comedies: those set in parks (filmed in Los Angeles’ Echo Park or Westlake Park), those staged against the background of public events (such as parades), and those filmed exclusively at the studio or in a combination of studio and location filming. A situation typically led to some sort of rally or chase, explosion, or the principal characters falling into a lake. The world of the Keystone comedies embraced the innocent mischief of the comic strips—hurling bricks, hitting rivals or police officers with mallets, kicking someone in the backside—and was populated with pretty girls, virago wives, and men with grotesque moustaches and beards.

Chaplin arrived at Keystone in early December 1913 and took a room at the Great Northern Hotel in downtown Los Angeles (he would later relocate to the Los Angeles Athletic Club). Sennett was startled to find Chaplin to be young because he had played older men on the stage. The actor was intimidated by the Keystone lot and its players: Sennett took me aside and explained their method of working. “We have no scenario—we get an idea then follow the natural sequence of events until it leads up to a chase, which is the essence of our comedy.” This method was edifying, but personally I hated a chase. It dissipates one’s personality; little as I knew about movies, I knew that nothing transcended personality.” (4)

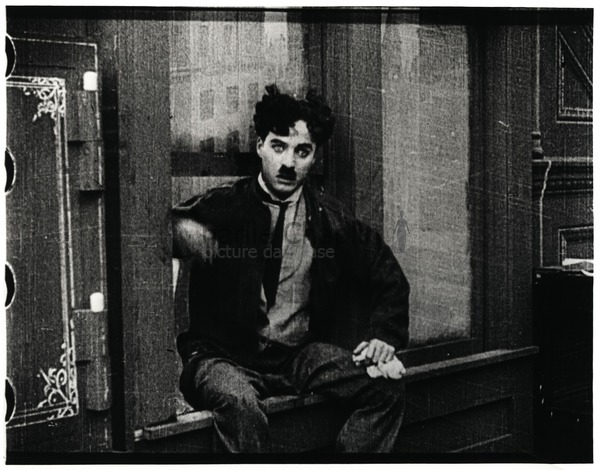

Chaplin’s first film was aptly titled Making a Living, in which Chaplin plays a “sharper;” he is an impoverished gentleman dressed in a top hat, frock coat, and monocle, with a drooping moustache of a typical stage villain and reminiscent of his Karno characters Archibald Binks in The Wow-Wows and the drunk in A Night in a London Club. The action of the film involves the sharper’s efforts to usurp the girlfriend and job of a news photographer (Henry Lehrman). Chaplin was accustomed to months of rehearsing and refining a comedy sketch with Karno. He quickly discovered that at Keystone, subtlety always gave way to speed. Inevitably, friction developed between Chaplin and Lehrman, who also directed Making a Living. Chaplin wanted a character-driven film with a slower pace, while Lehrman insisted on fast knockabout. He was further confused by why scenes were shot out of narrative order. He had no previous film experience and had always rehearsed and performed his theatrical work in the proper sequence. Chaplin was devastated when he saw the final product and discovered what Lehrman had edited, recalling: “Although the picture was completed in three days, I thought we contrived some very funny gags. But when I saw the finished film it broke my heart, for the cutter had butchered it beyond recognition, cutting into the middle of all my funny business.” (5)

Despite Chaplin’s low opinion of the film, Making a Living was well-received when it was released on February 2, 1914. The Moving Picture World, an important trade magazine, wrote “The clever player who takes the role of [the] nervy and very nifty sharper in this picture is a comedian of the first water, who acts like one of Nature’s own naturals…People out for an evening’s good time will howl.” (6)

The second film Chaplin made at Keystone, Mabel’s Strange Predicament, was the first film in which Chaplin donned the costume and character of the Tramp. (However, Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal., Chaplin’s third film, was the first Tramp film to be released.) Sennett evidently brought Chaplin into the cast of Mabel’s Strange Predicament as an afterthought, wanting him simply to enter a hotel lobby set and provide some comic business. He told Chaplin, “Put on a comedy makeup. Anything will do.” (7) Chaplin recalled in his autobiography:

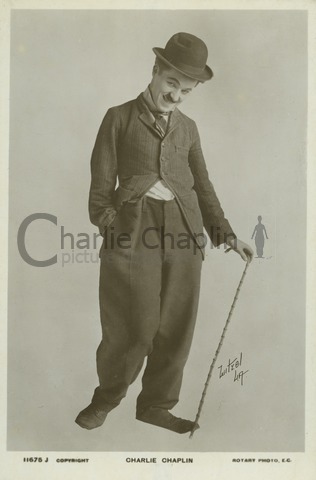

I had no idea what makeup to put on. I did not like my get-up as the press reporter [in Making a Living.] However, on the way to the wardrobe I thought I would dress in baggy pants, big shoes, a cane, and a derby hat. I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. I was undecided whether to look old or young, but remembering Sennett had expected me to be a much older man, I added a small moustache, which, I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the make-up made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on to the stage he was fully born. (8)

Encouraged by the laughs his Tramp was receiving, Chaplin explained the character to Sennett, “You know this fellow is many-sided, a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure. He would have you believe he is a scientist, a musician, a duke, and a polo-player. However, he is not above picking up cigarette-butts or robbing a baby of its candy. And, of course, if the occasion warrants it, he will kick a lady in the rear—but only in extreme anger!” (9) And thus, nearly spontaneously was born the most celebrated character in the history of motion-picture comedy.

In Mabel’s Strange Predicament, the Tramp is introduced, slightly tipsy, in the lobby of a hotel. In a typical Keystone plot, he becomes involved with a young woman (Mabel Normand) in a bedroom mixup. Later, the Tramp encounters Mabel in the corridor of the hotel dressed in her pajamas as she has managed to lock herself out of her room. The favorable reaction to Chaplin’s character by the seasoned Sennett company was a major victory for Chaplin, and Sennett allowed Chaplin’s first scene to go the entire 75 foot length (approximately one minute) without any editing, not the usual method at Keystone. Moreover, Chaplin’s Tramp character was reworked into the film’s scenario to appear in nearly all of its scenes from beginning to end.

Sennett was pleased, and so was Chaplin. He later explained, “As the clothes had imbued me with the character, I then and there decided I would keep to this costume whatever happened.” (10) Yet Chaplin was not entirely accurate. Although he used the costume for the majority of the Keystone films, he frequently deviated from it as well.

The Tramp character was influenced by tramp comedians of the British music hall as well as real-life tramps Chaplin had encountered in his childhood. A distinctive costume that fostered immediate recognition was traditionally an integral part of the success of a circus clown or music-hall comedian. The particular mixture Chaplin concocted—derby hat, toothbrush moustache, whangee (a type of bamboo) walking stick, baggy trousers, tight cutaway coat, and oversize boots (Chaplin’s actual shoe size was five; he originally wore size fourteen boots as the Tramp for a splay foot-walk)—was, when combined, his own creation.

Motion picture audiences first saw the Tramp on the screen in Chaplin’s third film for Keystone, Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal. (also directed by Lehrman), which was filmed on the Sunday afternoon of the following week in which Mabel’s Strange Predicament was filmed; but Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal. was edited and delivered to exhibitors first. Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal., a Keystone “event” comedy, was a split reel film (five hundred feet or less, and running approximately seven minutes) reportedly filmed in forty-five minutes to take advantage of a children’s car race at the oceanside resort of Venice, California. The plot, such as it is, is quite simple: the Tramp makes a nuisance of himself while a camera crew attempts to film the event. Although quite primitive, the film is historic not only because it represents the first appearance of the Tramp on screen, but also because it manages to record the first audience’s reaction to the character. The audience, of course, is the throng of spectators at the race who begin to notice this peculiar fellow causing trouble with a “camera crew.” At first the audience does not know what to make of the Tramp, then they begin to smile, then titter, and then laugh at his antics. In those brief moments of discovery, recorded for posterity, a comedic revolution was born. Pulitzer Prize-winning critic and author Walter Kerr observed:

He is elbowing his way into immortality, both as a “character” in the film and as a professional comedian to be remembered. And he is doing it by calling attention to the camera as camera. He would do this throughout his career, using the instrument as a means of establishing a direct and openly acknowledged relationship between himself and his audience. In fact, he is, with this film, establishing himself as one among the audience, one among those who are astonished by this new mechanical marvel, one among those who would like to be photographed by it, and—he would make the most of the implication later—one among those who are invariably chased away. He looked at the camera and went through it, joining the rest of us. The seeds of his subsequent hold on the public, the mysterious and almost inexplicable bond between this performer and everyman, were there. (11)

The genius of the Tramp character is that he is so human and familiar—he is one of us. It is remarkable that when directed by Sennett to find something funny to wear, Chaplin invented spontaneously that day in 1914 a symbol of all downtrodden and resilient humanity.

Chaplin took every opportunity he could to learn the business of making films and in his first efforts went beyond what was expected of him. He believed he could be creating the scenarios and directing his films better than Keystone directors Lehrman, George Nichols, and even Sennett. When he was assigned to take direction from Mabel Normand for the two-reel comedy Mabel at the Wheel, and Normand would not take his suggestions for his character’s comedy business, Chaplin confronted her and refused to work on the film for the rest of the day in protest.

According to Chaplin, Sennett at that point was on the brink of discharging him, but a telegram from the front office arrived clamoring for more Chaplin pictures. Sennett mollified Chaplin and Normand, and they completed Mabel at the Wheel amicably. Chaplin then asked to direct his own films, volunteering to deposit $1,500—his entire savings—as a guarantee if it could not be released. Sennett agreed and promised Chaplin a $25 bonus for each picture he made as a director. From his first films as director, Twenty Minutes of Love and Caught in the Rain, to the end of his year at Keystone, Chaplin directed many of the films in which he appeared, the notable exception being Tillie’s Punctured Romance. (12)

Chaplin’s Keystone films greatly differed from the gentle, sophisticated comedy that would be the hallmark of his later work. Yet, Chaplin injected into the Keystone comedies an acute understanding of character and movement that he had refined during his years in the British music halls, and a style of comedy that was polished yet appeared spontaneous at the same time.

Within weeks of the Tramp’s first appearance, the public had embraced him. Orders for the Chaplin Keystone films grew tremendously. It would only take a few months for Chaplin to be recognized as the most popular comedian in motion pictures, although his great fame and global stardom would not flower until after he signed with the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company in early 1915.

Once Chaplin had control over his own films, he began to enjoy his work at Keystone: “It was this charming alfresco spirit that was a delight—a challenge to one’s creativeness. It was so free and easy—no literature, no writers, we just had a notion around which we built gags, then made up the story as we went along” (13) he recalled in his autobiography. Most of the films were made in a week. A park, a hotel, a café, a dentist’s office, a bakery, a racetrack, backstage of a theater, or even a motion picture studio were the simple backdrops against which Chaplin’s inspired comedies unfolded.

Chaplin reprised his famed, fall-down drunk from his Karno days on several occasions at Keystone (Mabel’s Strange Predicament, Tango Tangles, His Favorite Pastime, Mabel’s Married Life, The Rounders). Chaplin’s years with Karno also prepared him well for the considerable athletic prowess required to perform the pratfalls and physical clowning of the Keystone comedian.

In the Keystone films, Chaplin imbues the Tramp with some of his famous traits: the waddling shuffle, the way he rounds a corner (making a sharp turn and skidding, holding one foot straight out and balancing on the other foot while holding his hat), his iconoclastic nose-thumbing (known as “cock a snoot”) at propriety and authority, and his twitching moustache. He can be seen drop-kicking a cigarette over his shoulder or laughing at the camera, behavior that would appear in subsequent films. The Tramp’s reactions to a situation were often more interesting than the situations themselves.

The New Janitor, a one-reel comedy, is the first appearance of pathos in a Chaplin film. Chaplin later recalled:

I can trace the first prompting of a desire to add another dimension to my films besides that of comedy. I was playing in a picture called The New Janitor, in a scene in which the manager of the office fires me. In pleading with him to take pity on me and let me retain my job, I started to pantomime appealingly that I had a large family of little children. Although I was enacting mock sentiment, Dorothy Davenport, an old actress, was on the sidelines watching the scene, and during rehearsal I looked up and to my surprise found her in tears. ‘I know it’s supposed to be funny,’ she said, ‘but you just make me weep.’ She confirmed something I already felt: I had the ability to evoke tears as well as laughter. (14)

Dough and Dynamite, a two-reel comedy directed by Chaplin, is one of the most successful Keystone films. Charlie and Chester Conklin are waiters at a bakery/café who are forced by their ill-tempered employer to man the ovens when the bakers go on strike. The film is filled with wonderful comedy touches, such as Charlie balancing a tray of bread loaves on his head and making doughnuts by flinging dough around his wrists like bracelets. In both characterization and structure, Dough and Dynamite is much finer than other comedy films of the time. According to Chaplin, the film took nine days to film at a cost of $1,800; because he went over his prescribed budget of $1,000, Sennett withheld his $25 directing bonus. Yet, the film grossed more than $135,000 in its first year. (15)

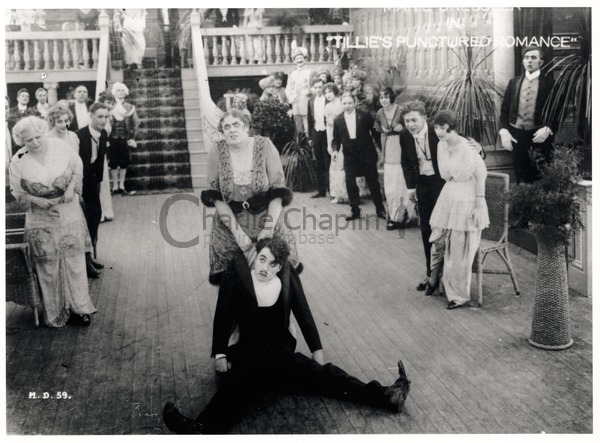

Tillie’s Punctured Romance is Hollywood’s first feature-length slapstick comedy. It was designed to star the famous stage comedienne Marie Dressler and was based on Tillie’s Nightmare, the 1910 Broadway hit that gave new impetus to her already impressive and lengthy career. Despite Chaplin having only a supporting role in the production, Tillie’s Punctured Romance benefited him more than anyone else when the film was released; nearly every motion-picture producer pursued him, wanting to sign him to a contract.

Directed by Mack Sennett and filmed in approximately forty-five days, Tillie’s Punctured Romance was tremendously popular when released, and Chaplin was singled out for his considerable work in making the film a hit. Chaplin, however, did not think much of the film. In his autobiography he dismissed it: “It was pleasant working with Marie, but I did not think the picture had much merit.” (16)

Chaplin’s personal life during his time at Keystone was almost nonexistent; he worked long hours, six days a week. Keystone player Peggy Pearce was apparently his first known love in Los Angeles. He met her, he remembered, in the third week at the studio and described her as his “first heart-throb.” However, Chaplin recalled, “At that time I had no desire to marry anyone. Freedom was too much an adventure. No woman could measure up to that vague image I had in my mind.” (17)

Chaplin’s last Keystone releases as actor/director were the sophisticated two-reeler His Prehistoric Past and the simple one-reel park film Getting Acquainted; both proved to be a strain on his concentration with so many business propositions required his attention. “I suppose that was the most exciting period of my career, for I was on the threshold of something wonderful,” (18) Chaplin later wrote. When Keystone sought to renew Chaplin’s contract, he announced to Sennett that he wanted $1,000 a week. Sennett responded that that was more than he earned himself, to which Chaplin replied, “I know it, but the public doesn’t line up outside the box-office when your name appears [sic] as they do for mine.” (19). The producer was unwilling to meet his demands. Sennett’s “fun factory” was indeed a factory, and Chaplin’s films only a part of its product. Sennett was willing to lose one key comedian after another, always hoping to replace them with someone good who would not disturb the economic equilibrium of the production line.

Chaplin refined Keystone slapstick and film comedy in general by slowing down the frantic pace of the films, giving them a rudimentary structure, and establishing a strong character, which he accomplished by drawing on his knowledge of stagecraft and pantomime. At Keystone he developed film technique and comic pacing for motion pictures that he would employ in some form or fashion for the rest of his career.

Although Chaplin’s relationship with the leader of the Keystone “fun factory” was often rocky, Sennett was a man of great enthusiasm if the work was good (a trait he shared with Fred Karno), and he afforded Chaplin the validation he needed. Ultimately, when Sennett gave Chaplin control over his own films, the men worked well together. Chaplin also admired Sennett’s belief in his own taste, a quality he instilled in the actor that helped to stimulate his creative imagination.

Chaplin’s tenure at Keystone is important because it marks the birth of the Tramp. More than just a great character, the Tramp embodies the heroic age of cinema. To many, he was film. As Lewis Jacobs wrote in 1939, “To think of Charlie Chaplin is to think of the movies.” (20)

An extraordinary aspect of Chaplin’s popularity is that he quickly became the most popular comedian in America and soon after throughout the world. It is staggering to consider that not only was there no radio, television, or internet to publicize or advertise the Tramp, but also the Keystone Film Company never credited its players by name on the films themselves or on its posters during Chaplin‘s tenure. To draw a crowd, many exhibitors merely cut out a cardboard figure of the Tramp and placed it outside the cinema with the phrase “I am here to-day.” (21)

Chaplin said, “All I need to make comedy is a park, a policeman and a pretty girl.” (22) He was confident in his own ideas. However, despite the advances in film comedy he made at Keystone, his Tramp character was far from fully formed. It would take several years for Chaplin to develop the emotional range that would mark his mature art. Yet this art began at Keystone. As Mack Sennett remembered, “it was a long time before he abandoned cruelty, venality, treachery, larceny, and lechery as the main characteristics of the tramp. Chaplin shrank his tramp in gradually diminishing sizes and made him pathetic—and loveable.” (23)

After completing over thirty-five films for Keystone of various lengths—split reels, one-reelers, and two-reelers, plus the feature film Tillie’s Punctured Romance—Chaplin emerged triumphant from his first experience in motion pictures. Without knowing his name, audiences embraced him as the most popular character in film comedy. Not a bad beginning for a young vaudevillian who thought he was summoned to a lawyer’s office to receive an old aunt’s inheritance.

Notes

1. Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (London, 1964), 145.

2. Chaplin’s contract with the Keystone Film Company, signed September 25, 1913, survives in the Chaplin Archives.

3. Chaplin, My Autobiography, 146.

4. Ibid., 151.

5. Ibid., 153.

6. “Comments on the Films: Making a Living,” Moving Picture World 19, no. 6 (February 7, 1914): 678.

7. Chaplin, My Autobiography, 154.

8. Ibid., 154.

9. Ibid., 154.

10. Ibid., 155.

11. Walter Kerr, The Silent Clowns (New York, 1975), 22.

12. The New York Motion Picture Company cut negative record and the Keystone Film Company releases list credit Joseph Maddern with the direction of Twenty Minutes of Love. However, in August 1914 Chaplin sent his elder half brother Sydney a list of twenty films in which he had appeared indicating six of them as “my own.” The earliest of the six was Twenty Minutes of Love, suggesting it as his directorial debut. Chaplin’s 1924 article “Does the Public Know What it Wants?” gives further confirmation that Chaplin considered Twenty Minutes of Love as his directorial debut. (Chaplin, “Does the Public Know What it Wants?” Adelphi 1, no. 8 (Jan. 1924): 702.) However, Chaplin wrote in his autobiography that Caught in the Rain was the first film he directed. Historians may never know with absolute certainty which film was Chaplin’s first as a director. Chaplin’s contribution to Twenty Minutes of Love may have been confined to story or comic business. Maddern may have provided supervision to Chaplin’s apprentice effort. It is suggestive that Chaplin remembered in his autobiography that the popular tune “Too Much Mustard” gave him the image for Twenty Minutes of Love and to which he choreographed situations.

13. Chaplin, My Autobiography, 164.

14. Ibid., 165.

15. Ibid., 167. Surviving documentation suggests production of the film occurred circa August 29-September 11, 1914. For a detailed discussion of this film, see Rob King, The Fun Factory: The Keystone Film Company and the Emergence of Mass Culture (Berkeley, CA, 2009), 91-96. Harry M. Geduld’s Chapliniana Volume I: The Keystone Films (Bloomington, IN, 1987) remains the most comprehensive evaluation of all Chaplin’s work at Keystone.

16. Ibid., 168.

17. Ibid., 167.

18. Ibid., 163.

19. Ibid., 169.

20. Lewis Jacobs, The Rise of the American Film (New York, 1939), 226.

21. Gilbert Seldes, The Seven Lively Arts (New York, 1924), 41.

22. Chaplin, My Autobiography, 169.

23. Mack Sennett (as told to Cameron Shipp), King of Comedy (Garden City, NY, 1954), 180.