The Score of The Great Dictator

In July 1940, Charlie Chaplin finished shooting The Great Dictator, but there was still plenty of work to be done. Directly after shooting, Chaplin continued editing the picture and as his son Charles Chaplin, Jr. recalled, “things did relax for Paulette [Goddard] and the rest of the cast … but not for Dad. Still the human dynamo, he turned his attention to composing.” As for his previous two films, City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936), Chaplin controlled the music for The Great Dictator by composing his own.

Robert Lewis, who played the part of the pharmacist in Monsieur Verdoux (1947), wrote in his autobiography that Chaplin gave some thought to working with Hanns Eisler on the music for The Great Dictator: “Charlie remarked how wonderfully ironic it would be if the German composer would contribute the music for The Great Dictator, which Chaplin was preparing, the leading character of which, Adolph Hitler, was responsible for Eisler’s exile from his homeland. Hanns bowed and said it would be an honor to work with such a film master.” However, after a brief exchange at a piano where Chaplin would repeatedly play an original, simple tune in exactly the same way, and Eisler would respond with other melodies or variations on Chaplin’s tune, the two artists were on different wavelengths and “it was clear that even Bach, Beethoven, or Mozart couldn’t shake Charlie from what he heard in his head.”

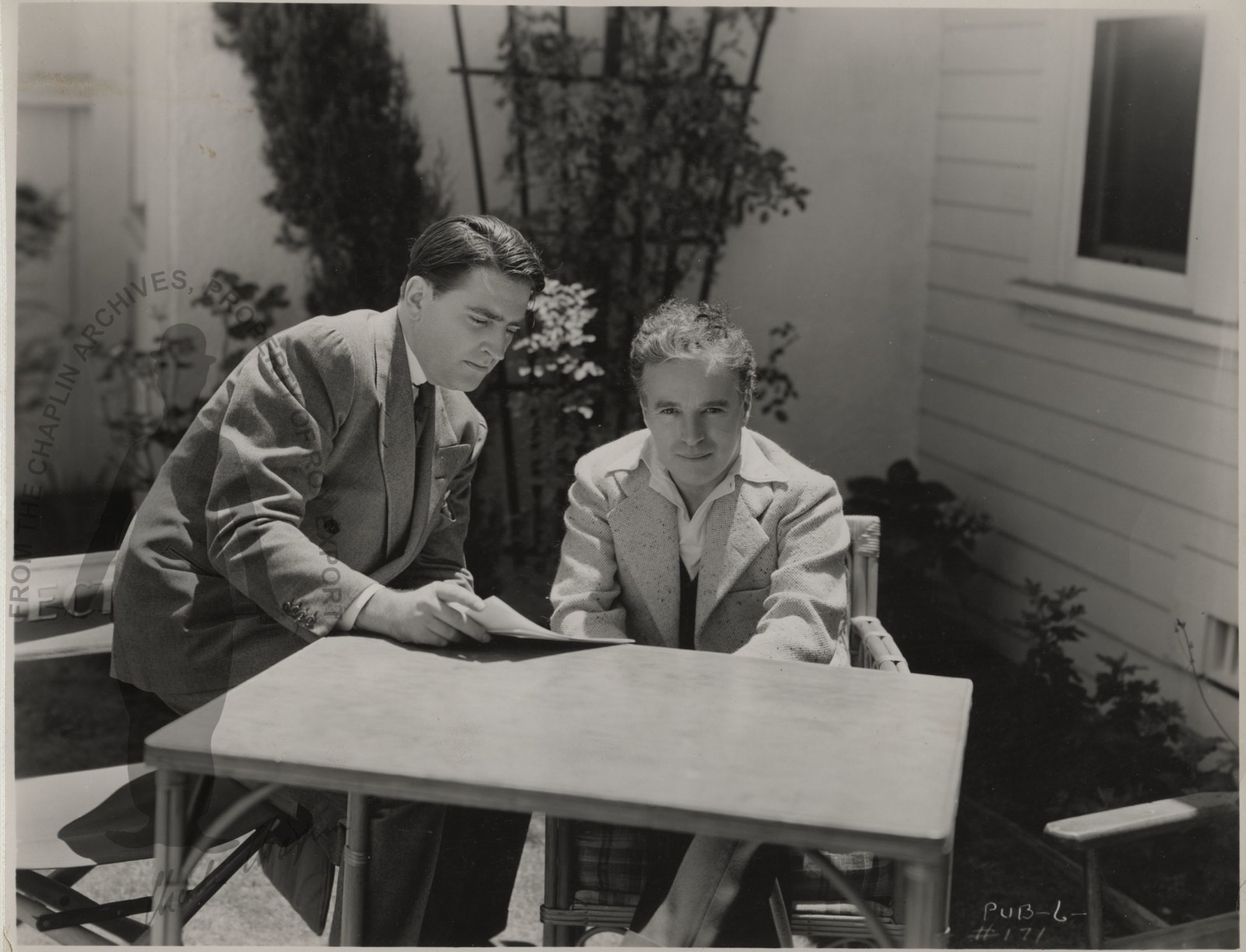

Chaplin collaborated on the score with 38-year-old American composer, Meredith Willson, perhaps best remembered today for The Music Man (1957), the hit Broadway musical for which he wrote the script, lyrics and music. According to Jim Lochner’s The Music of Charlie Chaplin, “in 1932 Willson became the music director for NBC’s Western Division. Over the next ten years, he directed as many as seventeen radio programs a week. Chaplin contacted Willson after hearing his second symphony, Missions of California, which premiered in April 1940 with Albert Coates and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.”

Willson provided insights about working with Chaplin on the music for The Great Dictator in an article published in the New York Herald Tribune on October 27th 1940: “We broke the picture into 70 musical sequences and spent weeks fitting original music to these sequences. Every note of music in the picture, except for an excerpt from Brahms’s Hungarian Dance No. 5, and a bit of Wagner’s Lohengrin third-act prelude, is original.”

Some years earlier, in relation to the score of City Lights, Chaplin modestly explained: “I really didn’t write it down, I la-laed and Arthur Johnston wrote it down (…) It is all simple music, you know, in keeping with my character.” However, Meredith Willson revealed that Chaplin’s contribution to music writing was much more than simply humming a tune and leaving the arrangers to write the music: “I have never met a man who devoted himself so completely to the ideal of perfection as Charlie Chaplin … I was constantly amazed at his attention to details, his feeling for the exact musical phrase or tempo to express the mood he wanted… Always he is seeking to ferret out every false note however minor from film or music.”

Charlie Chaplin himself said in a 1940 interview that “film music must never sound as if it were concert music. While it actually may convey more to the beholder-listener than the camera conveys at a given moment, still it must be never more than the voice of that camera.”

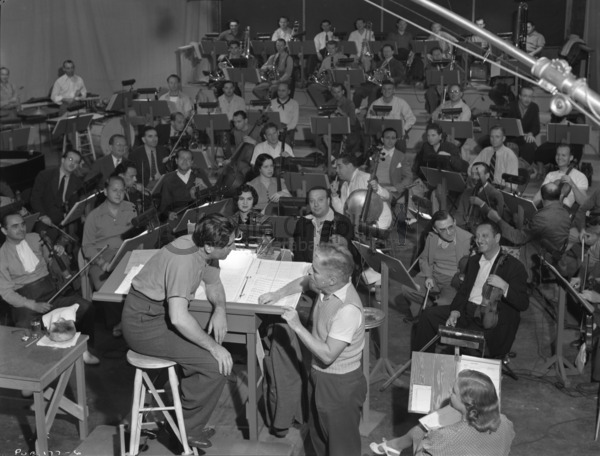

Charles Chaplin, Jr., 15 years old at the time, witnessed much of his father’s work on the score for The Great Dictator:

The musicians were actually musical secretaries taking Dad’s dictation. The music was always his. He would hum or play his tune and the musicians would take it down and then play it back for him. Dad would listen carefully. He has a wonderful ear. […]

It might take a number of tries before Dad had the tune to his satisfaction. He and the musicians not only worked long hours at home, but more long hours at the studio, where they used a Movieola so that a scene could be played, reversed and played again until the music to match it popped into Dad’s head. Once he had it in its entirety he would give the musicians a description of how he wanted it scored for each scene – the tempo, the rhythm, the style. […]

Sometimes when Dad described what he wanted the musicians would shake their heads, because Dad’s timing of a musical phrase to suit a bit of action was sometimes so unorthodox it threw them off. They would try to explain the technical reasons for not being able to give him what he asked for.

“Well, I’m not concerned about that,” Dad would say. “Just put it down here the way I want it.”

It was only after they’d done so that they could see that, though unorthodox, Dad’s dramatic instinct as it related to music was brilliant. So phrase after phrase, literally note by note, Dad and his valiant musicians worked their way through The Great Dictator. The musicians turned gray and were on the verge of nervous breakdowns by the time it was over, but whatever they suffered they couldn’t say that working with Dad was ever dull. He gave them a free performance at every session, because he didn’t just hum or sing, or knock out a tune on the piano. He couldn’t stay quiet that long. He would start gesturing with the music, acting out the parts of the various people in the scene he was working on, but caricaturing their movements to evoke a tonal response in himself. At those times his acting was closer than ever to ballet.

In his autobiography, Meredith Willson wrote of Chaplin, “I’ve seen him take a soundtrack and cut it all up and paste it back together and come up with some of the dangedest effects you ever heard – effects a composer would never think of. Don’t kid yourself about that one. I got the screen credit for The Great Dictator music score, but the best parts of it were all Charlie’s ideas, like using the Lohengrin ‘Prelude’ in the famous balloon dance scene.” Willson also recounts that Chaplin shot the scene where the barber shaves a customer to Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 5 to the sound of a recording. Willson and the orchestra had to record the piece in perfect synch to the edited scene. Amazingly, it only took two takes for the new recording to fit the action perfectly.

The premiere of The Great Dictator in New York City on October 15th 1940 was the only premiere that required engaging two side-by-side theatres because of viewer demand (the Capitol and Astor Theatres). According to the music cue sheets in the Chaplin archives, during the showing of the picture at certain theatres, an overture, an intermission and an exit were played. These tracks consist of musical numbers taken from the film as follows:

Overture:-

“Horses A-Manship” 3:05

“Pretzelberger March” 2:50

Intermission:-

“Ball Room Appasionato” 2:40

Exit:-

“Osterlich Bridge” 1:45

“Ze Boulevardier” 1:15

“Ghetto Sign” :20

“End Title” 1:00

The Great Dictator was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Original Score in 1941.

Article by Arnold Lozano