Chaplin and World War I

By Kevin Brownlow

British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, and author, Kevin Brownlow is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become interested in silent film at the age of eleven. This interest grew into a career spent documenting and restoring film. Brownlow has rescued many silent films and their history. His initiative in interviewing many largely forgotten, elderly film pioneers in the 1960s and 1970s preserved a legacy of early mass-entertainment cinema. He received an Academy Honorary Award in 2010, the first time an Academy Honorary Award was given to a film preservationist. His three-part documentary The Unknown Chaplin is a must.

This presentation was written for a public show in Bologna during one of the Cinema Ritrovato festivals. Kevin Brownlow has kindly agreed for us to publish it here so others may benefit from his research for presentations of their own.

Early in 1918, Chaplin made a short film for Harry Lauder’s Million Pound Fund For Maimed Men, Scottish Soldiers and Sailors. Lauder was a celebrated music hall comedian in Britain, who had lost his son at the front in 1916. For some reason, the film was never used for the purpose for which it was intended. A rough-cut and a great many outtakes exist but there is no evidence that it was ever finished. It has nothing to do with the war; it shows off Chaplin’s studio, set among the bucolic charm of old Hollywood, and it conveys the personalities of the two men as they impersonate each other.

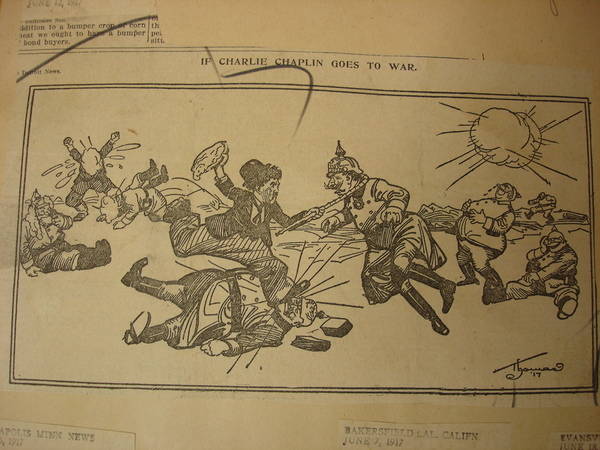

It is hard today to believe the scale of Chaplin’s popularity during World War I. Nothing illustrates it better than a newspaper cartoon headed HORRIBLE POSSIBILITY from 1919. It showed a soldier talking to a civilian:

‘It was a dreadful thing for us when Lord Kitchener died.’ (Kitchener was the British military leader at the start on WWI)

Civilian: ‘I dunno. It mighter been Charlie.’

Even today, when deference has disappeared, this seems almost sacrilegious.

By August 1914, Chaplin had already made two dozen short comedies for Mack Sennett’s Keystone studios and was experiencing his first rush of popularity. America remained neutral. But Chaplin was a British subject and it was the duty of British subjects in time of war to return immediately to the colours.

Had he done so, the chances of his surviving would have been slight. The name “Chaplin’ would have been merely a footnote in film history. We would never have seen The Kid, The Gold Rush, City Lights or Modern Times. Let alone The Great Dictator. And talking of The Great Dictator, his exact contemporary, Adolf Hitler, served throughout all four years unscathed. Can you think of a greater irony?

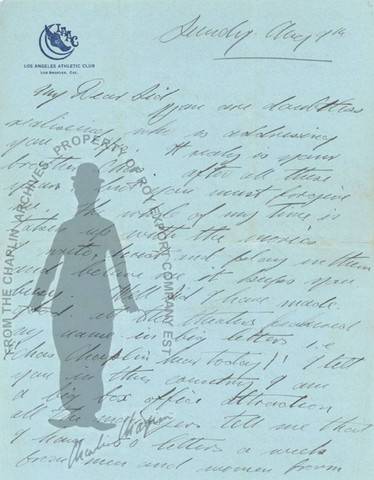

In David Robinson’s definitive biography, you can read one of Chaplin’s rare letters from this period. It was written after a meeting with Mack Sennett to discuss his contract. Chaplin had announced he would require $1000 a week. Sennett gasped – ‘Why, that’s more than I earn myself!’ Chaplin reminded him that it was not for his name that the public lined up outside cinemas. Here’s the letter, from August 9th 1914, five days after the outbreak of European war.

‘My Dear Sid [sic]…

Well, Sid, I have made good. All the theatres feature my name in big letters i.e. Chas Chaplin hear today. I tell you in this country I am a big box office attraction. All the managers tell me I have 50 letters a week from men and women from all parts of the world. [By 1922, he would be getting 10,000 a week, May 22 Pic PP 30] It is wonderful how popular I am in such a short time and next year I hope to make a bunch of dough. …You will like it out hear [sic]. It is a beautiful country and the fresh air is doing me the world of good. I have made a heap of good friends hear and go to all the parties etc. I stay at the best Club in the city where all the millionaires belong, in fact I have a good, sane, wholesome time. I have my own valet, some class to me, eh what? I am still saving my money and since I have been hear I have 4000 dollars in one bank, 1200 in another, 1500 in London not so bad for 25 and still going strong thank God. Sid, we will be millionaires before long. My health is better than it ever was and I am getting fatter. … Now about that money for Mother - do you think it is safe for me to send it while the war is on? … I hope they don’t make you fight over there. This war is terrible. … Well that’s about all the important news.

Your loving brother

Charlie’

There was no conscription in Britain as yet, and women used to hand white feathers to young men who were not in uniform. Propaganda portrayed such men as the lowest form of human life. A musical song became popular: ‘We don’t want to lose you, but we think you ought to go.’ Many men joined up because they could not bear the humiliation. As Chaplin became more famous, he was not only sent white feathers but subjected to threatening letters and attacks in the newspapers.

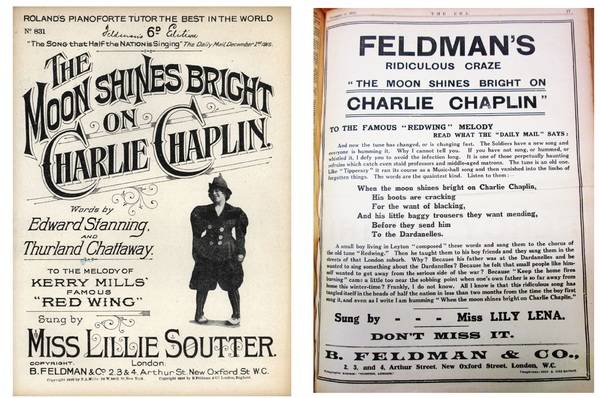

Despite his popularity, Chaplin’s apparent lack of patriotism created bad feeling in England. To those who had lost sons, husbands and fathers, what seemed his special treatment suggested the time-honoured gap between the privileged and themselves. At this period, Chaplin suppressed the story of his early life and claimed to have been born in Fontainebleau, the site of Napoleon’s palace. The public’s strange combination of affection and resentment expressed itself in a soldiers’ song, a parody of Redwing:

The moon shines bright on Charlie Chaplin

His boots are cracking

For want of blacking

And his little baggy trousers

They want mending

Before we send him

To the Dardanelles.

Chaplin’s reaction when he first heard the song was undiluted fear. As he told Alistair Cooke, ‘I really thought they were coming to get me. It scared the daylights out of me.1’

‘Had he gone to the front’, wrote Wm Dodgson Bowman, ‘the British army would have gained a recruit of indifferent physique and doubtful value; but it would have lost one of the few cheering influences that relieved the misery and wretchedness of those nightmare days2.’

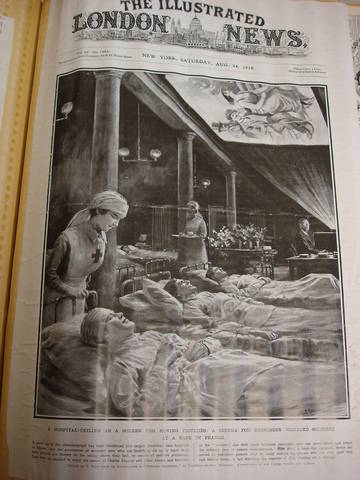

The troops felt Chaplin was the best morale booster they had. A Doctor in a neurological unit in France asked for signed photographs. In his letter he said, ’Nearly everyone has seen you in pictures; I will show a photo to a poor fellow and it may arrest his mind. He may say “Do you know Charlie?” and then begins the first ray of hope that the boy’s mind can be saved.’ Chaplin sent the pictures and said the letter ranked among his most treasured possessions.

In military hospitals, special projectors were installed so that Chaplin films could be shown on ceilings for men who could not sit up. A cinema manager said ‘Last week I was showing a Charlie Chaplin and a wounded soldier laughed so much he got up and walked to the end of the hall and quite forgot he had left his crutches behind. My assistant went after him and he said “That fellow Chaplin would make anyone forget his head. I never laughed so much in my life.3”’

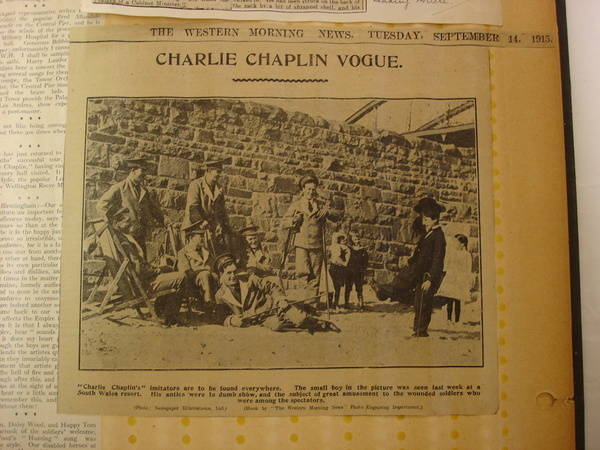

The appearance of a cut-out figure of Charlie with the slogan “HE’S HERE!” at the entrance to a cinema was enough to fill the seats. A detachment of the Highland Light Infantry, on the eve of their departure, captured one of these figures and carried it off as a souvenir to the trenches. These life size models were popular with the troops who would stand them on the parapet during an attack ‘so the Germans would die laughing.’

It has been alleged that the Germans were ignorant of Chaplin. That due to the British blockade, no American films reached Central Europe. This is backed up by Chaplin’s statement that when he visited Berlin, in 1921, in contrast to the mobs that greeted him everywhere else, only one man, a former prisoner of war who had seen his films in captivity, recognised him in a café, rushed over and kissed him. But it turns out that a great many Americans of German origin had answered the call to the Fatherland and had brought Chaplin souvenirs with them. Said an American newspaper: ‘In practically every enemy submarine brought to port, in every German trench, drawings and statues of Chaplin were found labelled satirically ‘America’s national hero’.4

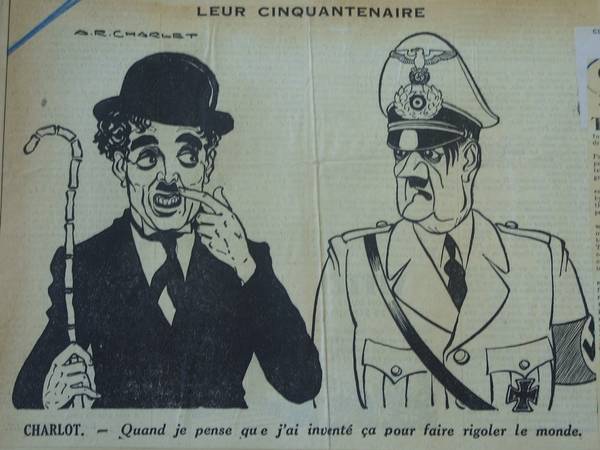

There is a rumour that Hitler cut down his walrus moustache to match Chaplin’s because he wanted to be loved. This is absurd. Hitler thought Chaplin ‘disgusting’ and furthermore a Jew, which he wasn’t. The toothbrush moustache was popular among German NCOs at the end of the war.

The Commander in Chief Home Forces, Sir John French, ordered troops to stop growing Chaplin moustaches. ‘It subverts the dignity of His Majesty’s troops in the field,’ he said5. Sergeants and officers would put subordinates on a charge – until the officers started growing them. Every military camp, every prison camp, had its Chaplin impersonator.

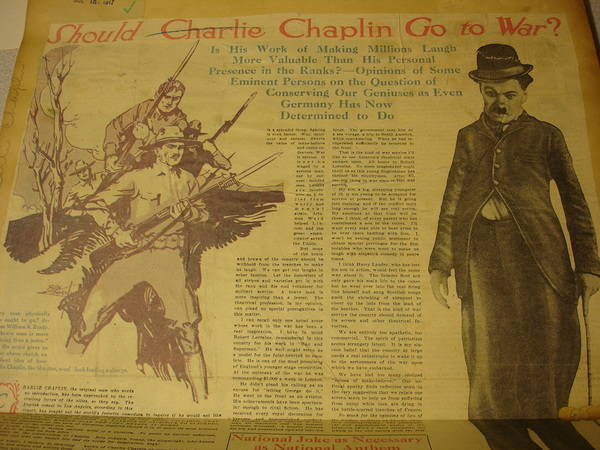

The fact that as Chaplin became the best-loved personality of the war, he also became one of the richest, gave him a certain respite. The British government cared no more for his artistry than for that of the thousands of other actors, writers, poets and painters who served at the front. But he was a willing source of finance for the British government. For as long as they could use him in this way, they left him alone.

In 1916, he signed with Mutual for more money than any entertainer in history - $670,000 a year plus bonus. John Freuler, head of Mutual, said that more editorial space was devoted to this salary than anything except the war itself6. The 20,000-word document included an element of war risk. Mutual insisted that Chaplin should not leave the United States within the life of the contract without the permission of the corporation. Imagine how that was received at the War Office!

One can safely assume that a sizable slice of that $670,000 went to the British government, for such a clause would not have been legally binding without their assurances. (In March 1917, for instance, Chaplin purchased a $58.000 block of Canadian war bonds7. In May it was reported that he had cabled $150,000 on the last day of Win the War Loan8. And Edna Purviance said “He simply pours thousands of dollars into England to help the war along9”. Mutual insured Chaplin’s life for $250,000.

The war risk created an outcry in the British press. The Daily Mail said ‘We have received several letters protesting against the idea of Freuler or any other American making a profit on the exhibition in this country of a man who binds himself not to come home to fight for his native land10.’

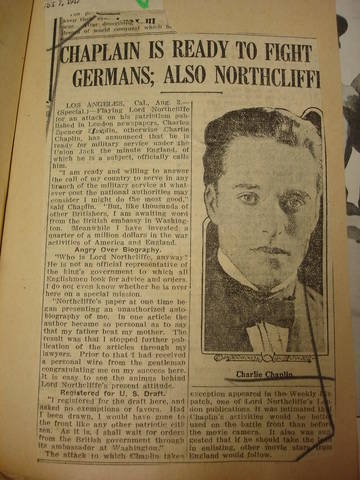

Chaplin was horrified when an interview he’d given in 1915 appeared, dressed up with fancy detail, as Charlie Chaplin’s Own Story. He instituted legal proceedings against the publishers but did not realise that syndication rights had been acquired by the Harmsworth Press in London. When Chaplin’s lawyer stepped in to suppress it, the head of Harmsworth, press baron Lord Northcliffe - the Wm Randolph Hearst of Britain - began an anti-Chaplin campaign.

‘Nobody would want Charlie Chaplin to join up if the Army doctors pronounced him unfit,’ wrote Northcliffe, ‘but until he has undergone medical examination he is under the suspicion of regarding himself as specially privileged to escape the common responsibilities of British citizenship. This thought may not have occurred to the much-boomed film performer, and he will not doubt be thankful that an opportunity for reminding him has been presented by the course of events.

Charlie in khaki would be one of the most popular figures in the army. He would compete in popularity even with Bairnsfather’s ‘Old Bill’. If his condition did not warrant him going into the trenches he could do admirable work by amusing troops in billets. In any case, it is Charlie’s duty to offer himself as a recruit and thus show himself proud of his British origin. It is his example which will count so very much, rather than the difference to the war that his joining up will make. We shall win without Charlie but (his millions of admirers will say) we would rather win with him.11’

Chaplin issued a statement to the press: ‘I am ready and willing to answer the call of my country… but like thousands of other Britishers, I am awaiting word from the British Embassy in Washington. Meanwhile, I have invested a quarter of a million dollars in the war activities of America and England. I registered for the draft here, and asked no exemption or favours. Had I been drawn, I would have gone to the front like any other patriotic citizen. As it is, I shall wait for orders from the British Government through its Ambassador in Washington.12’

The British Embassy responded: ‘We would not consider Chaplin a slacker unless we received instructions to put the compulsory service law into effect in the United States and unless after that he refused to join the colours… Chaplin could volunteer any day he wanted to, but he is of as much use to Great Britain now making big money and subscribing to war loans as he would be in the trenches…13’

Chaplin had made it clear that he had no intention of leaving Hollywood. He had built his own studio. He received prominent visitors, including such military figures as General Leonard Wood, who had organised the Rough Riders with Teddy Roosevelt in the Spanish-American war.

In July 1918 Chaplin signed his First National contract for $1 million plus a bonus upon signature of $15,000. On this occasion, the trade press hailed Chaplin as a national asset and suggested that if Chaplin’s joining up would put an end to the terrible sacrifice, only then should he be enlisted.

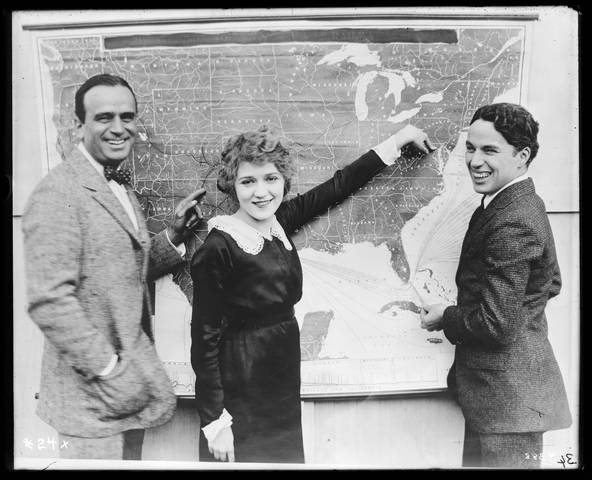

Chaplin’s motion picture activities were curtailed by his energetic campaigning for Liberty Bonds. This required a gruelling series of personal appearances. There were no microphones or amplifiers in those days; you had to project your voice and even so the chance of being heard by the eager thousands was negligible. He and his close friends Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks practised their speeches in a Los Angeles school, and a member of staff declared ‘They are the most charming people you could hope to meet.14’

They toured big cities, along with other stars, raising astonishing sums. When they arrived in New York, a process server from Essanay met them and Chaplin found himself sued for breach of contract15. Otherwise, the bond drive was an unalloyed success.

One lady donated $20,000 to the Red Cross for the privilege of sitting next to Chaplin at a gala dinner. This closeness led the Big Four – Chaplin, Fairbanks, Pickford and D W Griffith – to form United Artists in 1919, one of the more positive outcomes of the war.

With America in the war, the campaign against Chaplin became more vindictive. ‘His income could pay the expenses of a whole company of soldiers for a year’ reported Photoplay16. Chaplin went to a recruiting station and was placed in the fifth classification of the draft – unsuitable - rejected by army doctors for being underweight. Once this was announced, the campaign abated. A correspondent in England received a letter from Chaplin, explaining the situation:

‘I only wish I could join the English army and fight for my country. But I have received so many letters from soldiers at the front, as well as civilians, asking me to continue making pictures that I have come to the conclusion that my work lies right here in Los Angeles. At the same time, if my country thinks it needs me in the trenches more than the soldiers need my pictures, I am ready to go.’

In 1918 a treaty was finalised between Great Britain and the United States permitting the drafting of British subjects resident in America. Two hundred motion picture people in Los Angeles were affected. The London Times carried the news that Chapin had been drafted, and had waived his right to exemption. A few days later came a report that Chaplin would abandon his British nationality and join the U.S. Army in July – ‘a national calamity’, said The Bioscope.

Photoplay was doubtful that he would be taken – ‘his chest is only 26 inches’ they wrote17.

‘I feel as though I only want liberty to make three more pictures, and then I’ll gladly be going “over there”,’ said Chaplin. ‘But I’ve put a lot of money into my studio; I’ve assumed a lot of obligations, the future must be provided for, and I actually need the money that will come from three more pictures. I’m in the Southern California draft under the new treaty with England.’

To boost the Fourth Liberty Loan, Chaplin made a one-reeler called The Bond. It is a charming fragment of Chaplin whimsy, short scenes played against a stylised background of white cut-outs, as was common in revue. It illustrated the bond of friendship, the bond of love, the bond of marriage and ‘most important of all, the Liberty Bond.’

It was inevitable that Chaplin would make a comedy about war. But he was warned by D W Griffith, whom he greatly admired, not to do so until the war was over; He started it under the title Camouflage. He had been mulling over it for months, and when he was mulling over an idea, he could only propel that idea forward by trying out scenes on film.

It was planned as his first feature length comedy and it opened just as though he was continuing a film he hadn’t yet made – A Day’s Pleasure.

Charlie and his family return home and Charlie pops out of frame for a quick drink – wartime prohibition would have made this a topical joke. Also out of frame is his awful wife – her size is graphically suggested and life at the front would obviously be a rest cure by comparison.

For his medical, Charlie would have been stripped naked. Every man over 18 knew that but Chaplin could not possibly have shown it in 1918. This was his compromise. The fact that Edna Purviance appears as the secretary gave him trouble when she reappeared as the French girl later in the film. The medical examination featured Alf Reeves, studio manager, at the desk and Albert Austin as the doctor in one of several roles he was to play.

All this would eventually be discarded.

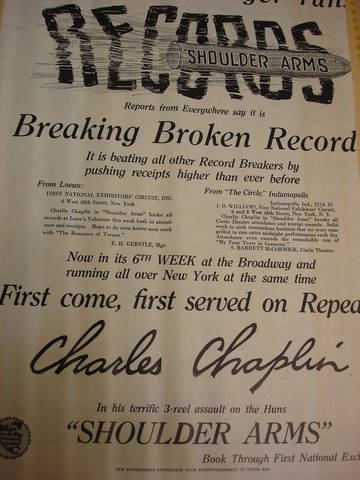

Begun in May 1918, the film came out just before the armistice. After which advertisements announced ‘Shoulder Arms has come at just the right time. People can laugh at it without any guilty feeling now.18’

Chaplin planned the film as a five reeler. He asked exhibitors if they would prefer a feature or a short and they all voted for the short, knowing how much more often it could be shown in a day. It was released in three reels. In the original ending, which historians Bardeche and Brassilach claim was banned and which Chaplin says was never shot19, the allies organise a banquet for Charlie. M. Poincaré makes a speech, and when Charlie rises to reply, King George creeps up and sneaks a button as a souvenir. More surprising, perhaps, was the fact that in some countries the capture of the Kaiser was removed.

You are probably familiar with Shoulder Arms, but a brief extract will remind you how cleverly Chaplin re-created the front. The set built for the trench is introduced, unusually for Chaplin, with a tracking shot – and that tracking shot reappears in almost every WW1 picture since from All Quiet to Paths of Glory. 1917 is one long tracking shot! Sensibly, Chaplin avoided giving Shoulder Arms the semblance of a newsreel, when the fun might have been hard to take. The uniforms approximate to the real thing – Charlie wears an American tunic, but the headgear looks more like an adaptation of Charlie’s bowler than the regulation steel helmet – a battle bowler, perhaps. Charlie is festooned with equipment which, on close examination, turn out to be non-regulation but extremely useful. These are ideal symbols for a film which would quickly lose its comedy if forced to be realistic. A mousetrap, implying the rats of the trenches and a cheese-grater indicating lice.

The Germans are not the lustful brutes of the Hun-hating feature films – quite the opposite. They are commanded by a tiny but tyrannical officer, played by Loyal Underwood, whose appearance must have caused immense mirth.

Cecil B De Mille suggested Chaplin delay its release because of its ‘bad taste’. Charlie agreed – he was exhausted and had lost all confidence in the film. He seriously considered scrapping it until he showed it to Douglas Fairbanks who found it hysterically funny.

The public reaction to Shoulder Arms astonished even Chaplin. It proved to be the greatest success of his career so far. And the excitement was, on at least one occasion, so violent that considerably more than box-office records were shattered. ‘Six doors torn from their hinges, seven lobby frames trampled to bits, a ticket box crushed beyond repair, a cast iron effigy of Charlie Chaplin battered to pieces, a special detail of policemen so badly bruised and manhandled that two bottles of Omega oil were used… are the outstanding features of two cyclonic days experienced by the manager of the Star Theatre, Elgin, Ill, when he played Shoulder Arms.’

Chaplin’s was the only war film from the entire war to be remembered with unqualified admiration.

When Chaplin visited London in 1921, one ex-soldier wanted to give him his medals for all he had done for the men at the front.

Charlie Chaplin was a true war hero, for his films did nothing but good.

Chaplin returned to the subject of war for The Great Dictator.

The Tramp and the Dictator is a film I made in collaboration with Spiegel TV in Germany. Association Chaplin had discovered rolls and rolls of colour film which Chaplin’s brother Sydney had shot of The Great Dictator in production. Michael Kloft of Spiegel suggested using it as part of a portrait of Chaplin and Hitler. They were born in the same week of the same month of the same year, and in public any rate, looked remarkably alike. So it seemed a good idea.

By the time United Artists was founded on 5 February 1919, the war was over. A gas attack at the end of 1918 had put Hitler into hospital. While convalescing, he had heard of the defeat of the German army on the Western front. He felt utterly betrayed. He had no job to go to, so, like so many, he stayed in the army. The revolutions of 1919 and 1920 propelled Hitler into the Nazi party.

In 1921, Chaplin returned to London for the first time. The city he knew as a poverty-stricken youth gave him a phenomenal welcome.

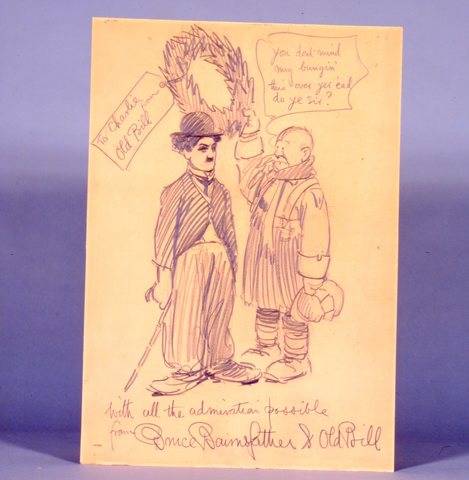

Bruce Bairnsfather, the great cartoonist of the war, a front line officer who created Old Bill and The Better ‘Ole played Chaplin the ultimate compliment. He drew Old Bill raising a laurel wreath over Charlie and saying ‘You don’t mind my bungin’ this over yer’ead, do ye sir?’ It is signed ‘with all the admiration possible’ from Bruce Bairnsfather and Old Bill.

And as for World War II, Albert Speer, Hitler’s armament’s minister and architect, wrote to Oona Chaplin, when he came out of prison, to say ‘I am still convinced that Chaplin’s contribution as “The Dictator” has been the best documentary about the Hitler period. And it will in all probability remain so.’

-

Cooke, Alistair, 1977, ‘Charles Chaplin’ in Six Men, Alfred A. Knopf, New York; The Bodley Head, London. ↩

-

Bowman, William Dodgson, 1931, Charlie Chaplin. His Life and Art, Routledge, London. ↩

-

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life And Art, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2001. p. 163. ↩

-

Macon, GA, News. February 9, 1918 ↩

-

St Paul Pioneer, March 25, 1917 ↩

-

Picture Play, June 1916, p. 125 ↩

-

LA Evening Herald, March 20, 1917 ↩

-

Photoplay, May 1917, p. 124 ↩

-

Motion Picture Magazine, April 1918 ↩

-

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life And Art, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2001. p. 161. ↩

-

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life And Art, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2001. p. 162. ↩

-

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life And Art, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2001. p. 162. ↩

-

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life And Art, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2001. p. 162. ↩

-

Generation of Motion Pictures, p. 188 ↩

-

Photoplay, July 1918, p. 109 ↩

-

Photoplay, September 1918, p. 104 ↩

-

Photoplay, May 1918, p. 85 ↩

-

Bioscope, 21 Nov 18 ↩

-

Chaplin, Charles, My Autobiography, London, The Bodley Head, 1964. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2003. p. 218. ↩