Dan James (and Charlie Chaplin)

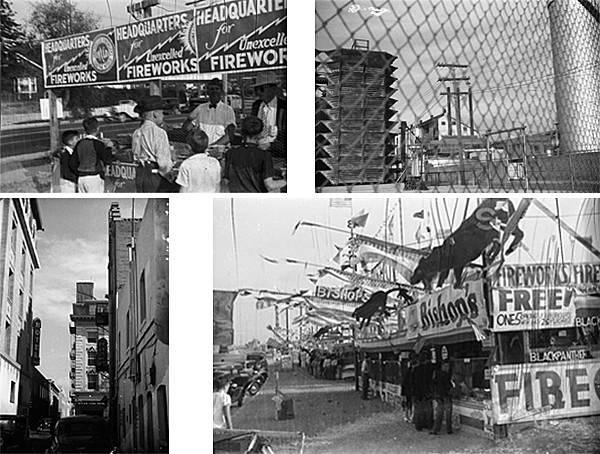

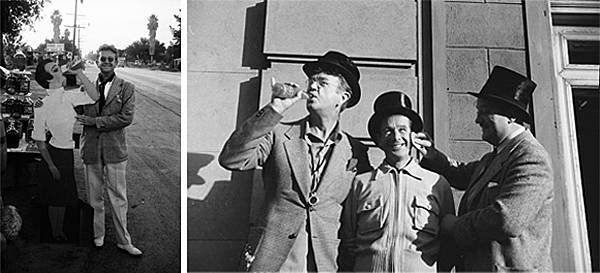

Recently the Chaplin office was lucky enough to acquire a series of photograph negatives from Dan James’s grand-daughter.1 The photos taken in the late 1930s reveal not only hitherto unknown details about the filming of The Great Dictator, but also glimpses of Californian industrial and natural landscapes, beaches, and people of the time.

Chaplin met Dan James on the Californian coast just south of Carmel at his father D. L. James’s home, Seaward2, an incredible house on rocks overlooking the Pacific Ocean, which still stands today.

Born January 14, 1911, Dan grew up in Kansas City, Missouri. His father was a successful businessman who dabbled in the arts and in particular in writing3. Dan graduated from Yale in 1933 with a degree in classical Greek, a considerable knowledge of the works of Karl Marx, and an interest in writing. While working the oil fields, he joined the Young Marxist League and was arrested for participating in a public demonstration sponsored by the league. According to the Jesse James heritage website, Dan’s father suggested he write about, rather than be active in, politics, and together they collaborated on a play – Pier 19 – about the 1934 General Strike of San Francisco.

In 1938, having separated from Paulette Goddard, Chaplin was a regular fixture at Pebble Beach, along the coast from Seaward. He spent many months there, with Tim Durant and occasional other houseguests, and although he proclaimed he did not want to be part of the Pebble Beach set, was soon, according to Durant, partying with them all.

Chaplin wrote: “Pebble Beach, a hundred-odd miles south of San Francisco, was wild, baneful and slightly sinister. I called it ‘the abode of stranded souls’. It was known as the Seventeen-mile Drive; it had deer roaming through its wooded sections, and many pretentious houses unoccupied and for sale; there were fallen trees rotting in fields full of wood ticks, poison ivy, oleander bushes and deadly nightshade — a setting for banshees. Fronting the ocean, built on the rocks, were several elaborate houses occupied by millionaires; this section was known as the Gold Coast. We rented a house set back from the ocean half a mile. It was dank and miserable, and when we lit a fire it would fill the room with volumes of smoke. Tim [Durant, recently divorced so also at a loose end] knew many of the social set of Pebble Beach, and while he visited them I tried to work. For days and days I sat alone in the library and walked in the garden, trying to get an idea, but nothing would come. Eventually, I deferred worrying, joined Tim and met some of our neighbours. I often thought they were good material for short stories — typical de Maupassant. One large house, although comfortable, was slightly eerie and sad. The host, an agreeable chap, talked loudly and incessantly while his wife sat without uttering a word. Since her baby had died five years ago, she seldom spoke or smiled. Her only utterance was good-evening and good-night. At another house built on the high cliffs overlooking the sea, a novelist had lost his wife. It appears she had been in the garden taking photographs and must have stepped backwards too far. When her husband went to look for her, he found only a tripod. She was never seen again. Wilson Mizner’s sister disliked her neighbours, whose tennis court overlooked her house, and whenever her neighbours played tennis she would build a fire and volumes of smoke would cover the court. The Fagans, an old couple, immensely rich, entertained elaborately on Sundays. The Nazi Consul, whom I met there, a blond, smooth-mannered young man, did his best to be engaging. But I gave him a wide-berth.”

There is no mention of D.L. James’s house, nor of Dan James, in Chaplin’s autobiography so we only have Dan’s version of how he met and came to work for Chaplin, at a time when “my writing was going nowhere, I was separating from my wife, and I was thinking of going to New York.” David Robinson, who interviewed James in the late 1970s, resumes: “They met on several occasions and Dan would hold forth about films and the war against Fascism. Chaplin in turn outlined his ideas for a Hitler film. When Chaplin returned from Pebble Beach to Hollywood at the end of the summer, Dan James took a chance and wrote to him saying that he was enthusiastic about the idea of the Hitler film, and would be very happy to be able to work on it in any capacity. ‘I went on packing my bags for the East though.’ Somewhat to his surprise a telephone call came from the Chaplin studio a few days later and he was invited to call and see Alf Reeves. Reeves warned him that Chaplin was very ‘changeable’ but that he liked him and would employ him on a salary of $80 a week, and put him up at the Beverly Hills Hotel until he could find somewhere to live.”4

James said: “My first evening [Chaplin] took me to Giro’s Trocadero Oyster bar – then we dined and he told me the outline of the story. The next day I went up and started to make notes… I think Charlie took me on because of my height, because my family had a castle out here, and because he knew pretty quickly I was a declared Communist so that my background and political preoccupations would keep me from selling him out for money.5” He also claimed, “I’m sure that Chaplin felt the Nazis could capture me and pull out my fingernails, and I would never turn against him.6”

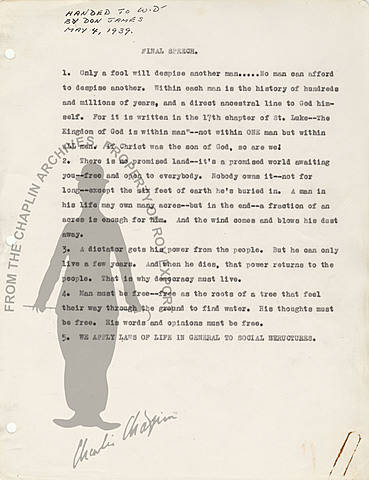

James joined the Communist Party in 1938, more as a romantic adventure than premature anti-fascism – “I was now supporting myself, and it was time to join my comrades in the working class.”7 However, lunching every day with his employer, and able to stay at Seaward whenever he wished, he was not quite working class! During the writing and shooting of The Great Dictator, James shadowed Chaplin, writing down everything he said. He would type up his notes, sometimes adding bits of his own invention, and Chaplin and he would work again on them the next day. Chaplin obviously trusted James completely, and the studio daily production reports show that sometimes James even directed certain scenes in Chaplin’s absence. The Chaplin archives hold many pages of notes in James’s handwriting, and/or possibly typed by James.

Of Chaplin, James told David Robinson:

“He did not read deeply, but he felt deeply everything that happened. The end of Modern Times, for instance, reflected perfectly the optimism of the New Deal period: already by 1934 and 1935 he had a sense of that. He had probably never read Marx but his conception of the millionaire in City Lights is an exact image for Marx’s conception of the business cycle. Marx wrote of the madness of the business cycle once it began to roll, the veering from one extreme to another. Chaplin presents a magnificent metaphor. Whether he was aware of the social meaning of this I do not know, but he got it. He had a sixth sense about a lot of things. In 1927 and 1928 for instance, he began to feel that the stock market was going mad, and he took everything he had and put it into Canadian gold.

Charlie called himself an anarchist. He was always fascinated with people of the left. One of the people he wanted to meet was Harry Bridges of the Longshoremen’s Union. I fixed up a meeting, and they took to each other immediately. Chaplin talked about the beauty of labor and described how in the islands he had heard the fishermen sing as they went out in their boats. Harry said ‘I think you would have found that it was the old men on the shore, the ones who had given up going to sea, who did the singing.’

Whatever his exact politics, Charlie had a position of revolt against wealth and stuffiness. He had a real feeling for the underdog… He was certainly a libertarian. He saw Stalin as a dangerous dictator very early and Bob [Meltzer] and I had difficulty getting him to leave Stalin out of the last speech in the Great Dictator. He was horrified by the Soviet German pact. His description of himself as an anarchist is as good as any. He believed in human freedom and human dignity. He hated and suspected the machine, even though it was the motion picture machine that gave him his life. I would say that he was anti-capitalist, anti-organization. And dammit, that’s the way people ought to be. When it came to Hitler it is easy to say, with hindsight, that Chaplin made too light of him. You have to remember that the film was conceived before Munich, and that Chaplin had undoubtedly had it in his head a couple of years before that. And the thought then was that this monster was not so awe inspiring as he appeared - he was a bit phoney and had to be shown up as such. Of course by the time the film appeared, France had fallen and we knew much more, so that a lot of the comedy had lost its point.”

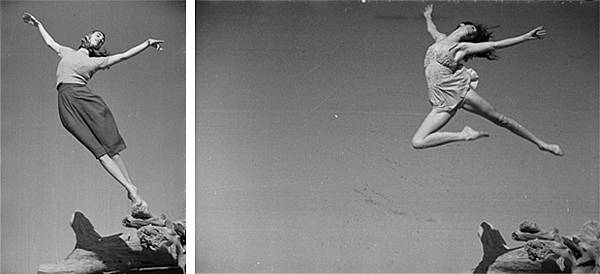

In 1940 James married his second wife, Lilith Stanward, a divorced ballerina with a daughter whom he later adopted.

The Party dominated their professional and social lives – meetings, fundraisers, benefits and balls for the Anti Nazi league, British and Russian War Relief, etc. When the USA entered the war after Pearl Harbor, James was unable to enlist because of a history of tuberculosis, but the Party felt that its writer members could serve the cause effectively at the typewriter. His play Winter Soldiers, the story of a united anti-Nazi movement in Central Europe8, won an award9 in 1942, even though with 42 speaking parts it was too expensive to stage, and in 1944 he and Lilith were co-authors of the musical comedy Bloomer Girl, a play written by Lilith after a Party-endorsed workshop on women’s rights.10

Unsurprisingly the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed the couple in 1951, although they had left the Communist Party in 1948, disillusioned with the way the movement had developed. Both took refuge in the Fifth Amendment and refused to name names. Thereafter, like so many other writers at the time, James continued his work but under a new name - Daniel Hyatt. He participated (uncredited) in the screenplay of the 1953 film directed by Eugene Lourié The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms11, and in 1958 co-wrote with Lourié the screenplay for Revolt in the Big House. They then both worked on the scenario of Behemoth the Sea Monster, released in 1959. “Daniel Hyatt” next collaborated with writer Robert L Richards, (also writing under a pseudonym - John Loring) on Lourié’s science fiction monster film Gorgo. That makes quite a lot of monsters.

Under the name “Daniel Santiago” Dan James published the novel Famous All Over Town in 1983, for which he was awarded the Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation prize of $5,000 by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Wishing to remain anonymous he did not attend the award ceremony, and since he refused to supply any personal information to his publishers, they were unable, though they suggested it, to submit the book for the Pulitzer Prize. The citation for the Rosenthal award read: “Famous All Over Town adds luster to the enlarging literary genre of immigrant experience, of social, cultural and psychological thresholdcrossing… The durable young narrator spins across a multicolored scene of crime, racial violence and extremes of dislocation, seeking and perhaps finding his own space. The exuberant mixes with the nervewracking; and throughout sly slippages of language enact a comedy on the theme of communication.”12 Supposedly written by a young Mexican with intimate knowledge of street culture, in 1984 the true identity of Daniel Santiago was revealed by John Gregory Dunne in the New York Review of Books as Dan James – Santiago of course is James in Spanish – a 73-year-old white American. Controversy ensued, with claims of literary fraud for misleading readers into believing that the author was of Mexican descent, but the book continued to be praised for the truth of its observations.

Daniel James died in Monterey at the age of 77. He and Lilith were living at Seaward. He was survived by two daughters.

-

The Chaplin office thanks Nellie James, Martha Diehl, and Lisa Haven for her help with the acquisition. ↩

-

designed by Charles Greene, pioneer of the Arts and Crafts movement in Southern California ↩

-

According to online records, the State Historical Society of Missouri holds four manuscripts written by Dan James Jr: Survival, In Which the Son of an Ancient People Sees a Strange Sign, Ol Paul, The Mighty Logger, and last but not least, Life and Times of Frank and Jesse James – his father’s first cousins. John Gregory Dunne however writes that it was DL James senior who worked for years on the latter project so perhaps Dan re-worked his father’s draft. https://collections.shsmo.org/manuscripts/kansascity/k0018.pdf ↩

-

David Robinson, CHAPLIN : His Life and Art, Penguin, London, re-edition 2001 ↩

-

Interview with David Robinson, 1970s ↩

-

Quoted by John Gregory Dunne, An American Education, p 30 ↩

-

John Gregory Dunne, An American Education, p 31 ↩

-

John Gregory Dunne, An American Education, p 34 ↩

-

The Sydney Howard Memorial Award, given by the Playwrights Company to the young American playwright showing the most promise ↩

-

John Gregory Dunne, An American Education, p 35 ↩

-

Eugène Lourié collaborated with Chaplin as Art Director on Limelight in 1952 ↩

-

John Gregory Dunne, NY review of books, Aug 16th 1984 ↩