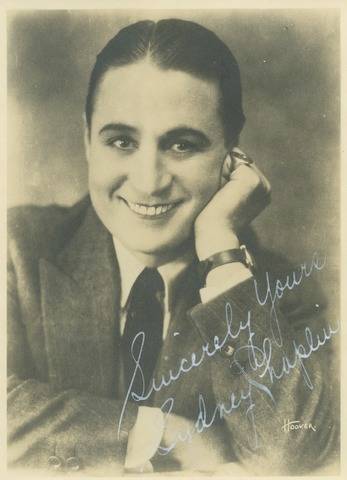

Syd Chaplin’s Father: A New Insight

Article by Barry Anthony, author of Chaplin’s Music Hall: The Chaplins and their Circle in the Limelight, November 2023

When Charles Chaplin was young his mother told him many colourful stories - some rooted in personal experience, but others springing from her extremely fertile imagination. For a child it was almost impossible to unpick fact from fantasy. One tale which puzzled and piqued Charlie to an equal extent was that his half-brother’s father was a wealthy nobleman. On turning 21 years of age, Sydney would inherit £2000 (£300,000 in 2023 terms) – so mother said. But Sydney’s great expectations were not fulfilled, and his father remained a shadowy figure whose identity and social status have mystified biographers for many years. In the absence of hard facts some authors have even created their own mythology by relating how Hannah had eloped to South Africa with a Jewish bookmaker named ‘Sydney Hawkes’. Only recently has it been possible to say with a degree of certainty that Sydney’s father was an affluent London businessman whose lifestyle and relationships were the very stuff of Victorian melodrama.

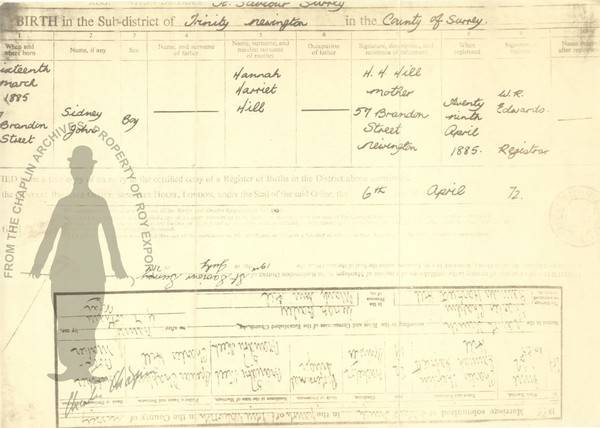

Sydney was four years older than Charlie, born on 16 March 1885. Completed two days later his baptismal certificate consists of a series of simple facts which tell a complicated story. His mother, recorded under her maiden name ‘Hannah Harriet Hill’, is living at 57 Brandon Street, Walworth, which proves to be the home of distant relatives. Sydney is named as ‘Sidney John’, while, in the space provided for parents, Hannah’s name is also linked to a ‘Sidney John’ which has been crossed through. A simple mistake, perhaps, or possibly a clue to the infant’s parentage.

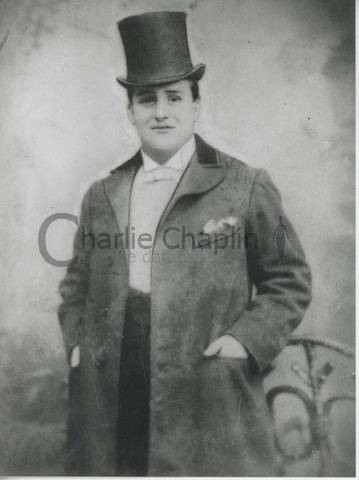

Although only 19, Hannah had already established herself as a popular performer in the highly competitive world of Victorian music hall. For a female singer and dancer to achieve any degree of success, talent, determination, and physical charm were prerequisites. In addition, a degree of financial support was a major bonus. It seems that in the person of Sidney John Hawke, Hannah had found a wealthy sponsor or protector at the earliest stage of her career.

Hannah’s first traceable appearance under her stage name (the spelling frequently varied) occurred in the theatrical newspaper The Era on 31 March 1883. Her professional advertising ‘card’ announced:

MISS LILLIE HARLEY

AMPHITHEATRE, PORTSMOUTH

Immense success

Communications to

“ANTELOPE,” Lorn-road, Brixton

Until recently her reason for using the ‘Antelope’ as an address was unclear - perhaps she was employed there or had taken lodgings in this historic South London tavern. New research, however, has shown that she had a far more personal and life-changing motive. It has been established that from November 1882 to June 1883 the holder of the pub’s licence was none other than Sidney John Hawke (see South London Press, 18 November 1882, p. 11). Both Lisa Stein Haven (author of Syd Chaplin: a Biography) and I had suspected that this particular Hawke was a person of interest, but the new information is the first evidence that directly links him with Hannah.

In My Autobiography Charles Chaplin remembered that his mother often referred to her visit to South Africa with the mysterious ‘lord’: ‘living in luxury amidst plantations, servants and saddle horses’. Although nothing has been discovered about a possible stay in Africa, had Hannah lived with Sidney John Hawke her life would still have been far grander than with her own impoverished family. The ‘Antelope’ tavern was set in a street of solidly middle-class villas and offered such benefits as a concert room, stables, kitchen and pleasure gardens and ‘a most comfortable family residence’ (The Era, 22 November 1884, p. 13). But Sidney could easily have secured accommodation elsewhere. His father, John Hawke, was a prosperous builder and property developer, occupying the imposing ‘Kent Villas’, 216 Lewisham High Road. Although it seems unlikely that Sidney would have moved his teenage mistress into the family home, he would presumably have had access to various addresses that both he and his father were selling.

Sidney John Hawke was born in Hatcham (an archaic name for New Cross in the London borough of Greenwich) in 1859. While their birthplaces were located only three to four miles apart, the environments in which Sidney and Hannah grew up were entirely different. Hannah’s father was a journeyman bootmaker who dragged his family from one squalid lodging to another. Sidney’s was a master builder who employed labourers and craftsmen at work and domestic staff in his home. It is not possible to discover how Hannah and Sidney met, but it seems highly likely that he assisted her progress as a music-hall performer. It is perhaps significant that one of her earliest engagements (only two weeks after the ‘Antelope’ advert) was a four-week stint at a leading London venue, the Hungerford Hall. Sidney might have purchased costumes and songs, subsidised her appearance or even rented the services of that appreciative group of theatrical enthusiasts, the ‘Claque’.

One small clue suggests that Hannah and Sidney did visit South Africa in 1883. Sailing from Southampton to Cape Town, via Madera, on 6 September, the Union Steamship Company’s steamer ‘Mexican’ was reported to be carrying 64 passengers. Among those spotted by an on-board journalist were an opera singer, Mademoiselle Bredelli; a distinguished soldier, Major Kent Johnson; and a nobleman, Count Lagerberg, who was commonly referred to as ‘Count Lager Beer’. Although two other travellers failed to attract the attention of the keen-eyed reporter, a passenger list published by the periodical The Colonies and India, shows that also sailing to South Africa were a ‘Mr. and Mrs. S. Hawke’. Of course, another couple possessing a more legitimate claim to the title may have been on their way to Cape Town. But it may be significant that in otherwise fairly well documented careers, neither Hannah nor Sidney can be located in the UK during the period May 1883-May 1884. Perhaps Hannah was pregnant and an extended vacation in a distant country was a matter of convenience.

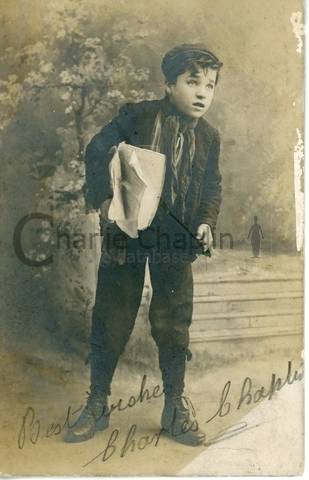

The year 1884 brought with it two matters of life and death. In the summer Hannah became pregnant and in November Sidney’s father died, leaving a personal estate of over £34,000 (over £5,000,000 in 2023 terms), mainly in trust for his wife Anne. Such a change in circumstances may have brought about an end to Hannah’s relationship with Sidney, or she may simply have transferred her affections to the variety performer Charles Chaplin. Whatever reason, only a month after Sydney’s birth, Hannah and Charles embarked on a marriage which was to lurch from one catastrophe to another. At first, they toured the UK together, appearing as solo acts on the same music-hall programmes. As time went on Hannah’s billing dwindled while Charles became a popular and well-known performer. Hannah’s sister also entered ‘the Profession’ and under the name ‘Kitty Fairdale’ soon overshadowed her older sister. Despite her successful relatives and wealthy ex-lover Hannah drifted into the cycle of poor health and impoverishment so graphically described by her son Charles.

It seems that Hannah’s life would have been hardly less miserable had she remained with Sidney. Before running ‘The Antelope’ he had traded as a coal and coke merchant with his brother-in-law in the Thameside district of Deptford. Throughout the remainder of the 1880s he had been involved with various public-houses. On his arriving on England’s south coast in 1889 the local newspaper reported:

‘Mr. Sidney John Hawke, who has formerly occupied premises at Stroud and Brixton, and has recently been residing at Brighton, applies for protection in response of the Egremont Hotel, Brighton…’ Worthing Gazette, 15 January 1890, p. 5.

In July Sidney gave up the tenancy of the ‘Egremont Hotel’ to embark on a new career. On the 19 October 1890 an advert in the Daily Telegraph announced:

‘PUBLIC HOUSES or HOTELS.- IF you think of taking above consult Mr. S. J. HAWKE, Hotel Valuer, of 5, Bloomsbury-square, who will give you sound advice free of charge. Mr. S. J. Hawke has been proprietor of houses in London and country, and can advise from experience in the trade.’ Daily Telegraph, 10 October 1890, p. 6.

What we can glean about Sidney’s personality does not make for easy reading. His connections with the public house trade would certainly have brought him into contact with a wide sector of society who did not subscribe to conventional, largely middle-class, morality. Not particularly damning, but his own behaviour was often cruel, callous, and aggressive. Such negative qualities were all displayed following his marriage to Catherine Julia Pearce. On registering their wedding in 1891 Sidney gave his address as his mother’s home (now changed to 200 Lewisham High Road) while Catherine stated that she had previously lived at the innocuous sounding ‘St. Hilda’, Burgess Hill, NW London. In fact, ‘St. Hilda’, proved to belong to Doctor Frederick Aubyn Monks who in 1908 featured in a sensational case at the Old Bailey when he was accused of committing a series of abortions on his young mistress. Aged 22, Catherine had previously lived with a wealthy brewer, William Henry Dusildorff, bearing him a child.

Sidney was incensed when Catherine and her former lover remained on friendly terms and his violent response to the situation led to an appearance at Bow Street court on 19 May 1892. He had sent menacing postcards to Dusildorff and his sister. One read:

‘Even your telegrams and correspondence are in safe keeping. At your every meeting you will be followed and watched. You shall bitterly regret it. I am not to be trifled with. It is owing to you and another that I am separated from my wife and my home broken up. The other [a man named ‘Mason’] has paid the penalty and will show it to his dying day. Your turn shall come in due course. Shortly you shall pay for it.’ Weekly Dispatch, 22 May 1892, p. 5.

Sidney was bound over to keep the peace, a commitment that he manifestly failed to honour. Just over a year later, he was again in court, charged with assaulting his wife. In her evidence Catherine reported that his abusive behaviour had continued throughout their marriage and that she had left him on two occasions. Following his repeated requests, she had returned for a third time, but at midnight on 28 September 1893 he attacked her violently and locked her out of their Balham Hill home in South London. Caroline was left all night in the torrential rain, without a hat, coat, or boots. When a police constable intervened, Sidney responded by throwing her footwear out of the window. Sidney was fined five pounds and Caroline was condemned to another six years of brutality and humiliation. For some reason she endured Sidney’s behaviour until December 1898 when she initiated divorce proceedings on the grounds of cruelty and numerous episodes of adultery. Most recently (in July 1898) he had stayed with an unknown woman at the ‘Royal Forest Hotel’, Chingford, Essex, and the ‘Ship Hotel’, Southend on Sea, in the same county.

Beyond his own ‘Home Sweet Home’ Sidney appears to have been a genial and entertaining individual, a typical representative of that louche group of socialites known, somewhat prosaically, as ‘men about town’. Even when describing his threats of extreme violence against Dusildorff, a reporter for the Kent Times (26 May 1892) still considered it appropriate to mention one of his merry jaunts:

‘We rather think Mr. Hawke is not altogether unknown in Maidstone. And a prominent licensed victualler could tell of a very pleasant sojourn in his company at a fair seaside place not a hundred miles from Worthing. We have heard that cards were mentioned on that occasion, with the usual result, so far as Boniface [i.e., an innkeeper] was concerned.’

Sidney’s presence continued to be felt by the Chaplin family over a period of years. During the early 1890s Hannah had confided his name to Leo Dryden (the father of her third son, Wheeler Dryden) and both Sydney and Charles appear to have understood the nature of the situation. Charles remembered that when he was appearing with the Karno troupe at the Folies Bergère in 1909, he was approached by a stage-struck ‘cousin of my brother’s, related to Sydney’s father’ [i.e., Sidney Hawke’s nephew]. During his stay in Paris the unnamed relative, treated Charles to lavish entertainments. Chaplin explained ‘he was rich and belonged to the so-called upper class’. In Syd Chaplin Lisa Stein Haven tells how a stranger presented Sydney with an ornate, crested signet ring, stating that it was a gift from his father. And in later years Charles wrote to the journalist R. J. Minney that he had seen a photo of Sydney’s father and that they looked alike.

Hawke inherited £6400 (over £900,000 in 2023 terms) when his mother died in 1911, her estate apparently diminished, possibly by Sidney himself. He had continued to be involved with the catering industry, at one time running a popular haunt of music-hall performers, ‘The Anchor’ at Shepperton on Thames. By the time of his death at the age of 66 in 1925, he would have seen Syd Chaplin become an internationally famous film comedian, feted as the brother of the world’s most famous man.

The identification of Hawke as Sydney’s probable father further deepens the mystery of why Hannah endured such poverty while knowing so many people who could have provided her with support. However, one aspect of Hannah’s early life is now much clearer. Sydney Hawkes, the Jewish bookmaker or cockney conman, was a fictional character, largely the construct of biographers faced with an irritating absence of information. Charles Chaplin may have been misinformed about the social standing of Sydney’s father, but he accurately recorded his mother’s colourful story that Sidney John Hawke was possessed of a considerable fortune.

Barry Anthony is the author of Chaplin’s Music Hall; the Chaplin’s and their Circle in the Limelight, published by I. B. Tauris in 2012, and Pimple’s Progress: Fred Evans, Britain’s First Film Comedy Star, published by McFarland in 2022.