Tango Entanglement

An article by Lisa Stein Haven, 2006

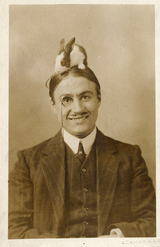

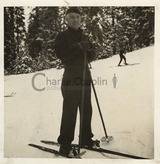

Somewhere I read that the tango was Charlie’s favorite dance step. We all know that Charlie Chaplin is reputed for his grace and balleticness, which is not surprising, really, when you consider that clog dancing was one of his earliest sources of remuneration. So, he’s often mentioned in the same breath with styles of dance like ballet, which he commemorates in the dream sequence of Sunnyside (1919) and in the whole of Limelight (1952), for instance, or the waltz, for which he commands some attention (albeit comic attention) in important scenes in The Count (1917) and, of course, in The Gold Rush (1925). But what of the tango? Countless aspects of Charlie’s life have been captured on film, of course, in newsreels, in cameos—such as in Turner Classic Movies’ recent airing of Souls for Sale (1923)—and in his own many films, but I don’t think I’ve had the pleasure of seeing him dance seriously in any of them and certainly not dancing the tango. This may not seem like a big deal, except that the reports of his performances make it so.

You may be saying to yourself, yes, but she’s forgotten Tango Tangles, released by Keystone Studios on March 9, 1914. True, the name suggests that we, the viewers, may be treated to some sort of tango-related antics in this film, but, in fact, the “tangles” usurps the “tango” in importance here. As Thierry Georges Mathieu writes in Revue no. 4 of his La Naissance de Charlot series, “These last tango scenes are the only ones in the entire movie … which it ironically takes its name from. The title seems to have been chosen for commercial purposes, more so to attract an easy audience looking for new thrills rather than dealing, whether favourably or not, with this popular dance which was controversial at the time.” (21).

But what exactly is a tango and how would we know whether or not it was being exhibited in Tango Tangles anyway? I like ballroomdancers.com’s simple definition, because I think it says a lot. The tango is a dance in 2/4 time, originally from Argentina, and is “characterized by catlike walking action and staccato head movements.” Sounds like the perfect dance step for a consummate pantomimist! In fact, the tango had only entered the United States and its consciousness a few years before this film. The 1920 book, Handbook of Ball-Room Dancing, by Paymaster-Commander A. M. Cree, RN., of all people, notes that “In 1912–13, when the ‘Tango’ first came among us, expositions were given on nearly every music-hall, with the result that a few self-styled experts were rushing up and down drawing-rooms, executing vigorous half-moons, scissors, and introduced mattchiche steps into their gyrations, with the result that the dance was immediately voted ‘taboo.’”(8-9). Dancers Irene and Vernon Castle, who often demonstrated their talents on the Broadway stage are given credit by some for the step’s introduction here; others claim it was New York City dance instructor Maurice Mouvet who brought it back from his Paris vacation. Whatever circumstances surround its introduction, however, the tango’s exotic and intoxicating allure failed to be squelched even by the advent of World War I, a fact that probably predicted its continuing popularity today.

Charlie himself began to be known for his tango prowess in the early 1930s. The press coverage of his European tour included a flurry of articles on his skill, especially after he had met up with May Reeves, a self-proclaimed acrobatic dancer, on the French Riviera in June 1931. The San Diego Blade reported on June 30th that

wearing the French Legion of Honor in his coat lapel, Charlie Chaplin and his Austrian brunette find, Mary [sic] Reeves, showed the interested spectators at the Casino how the tango should be tangoed. . . . Every night for weeks he has been dining at a little table for two in the center of the outer rim of the dance floor of the Juan-Les-Pins Casino and facing the two orchestras and the stage between them. “I prefer tangoing to any other form of dancing,” he told a reporter. “It is the most graceful dance of all and Spanish and Argentine music has more expression than all jazz in the world.”

From May’s own account in Charlie Chaplin intime (1935), it appears that the tango entered into their conversation within the first few minutes after their initial meeting:

“Can you tango?”

“The tango is my trade. […]

“Come into the next room; we’ll dance.” (Constance Brown Kuriyama translation 19)

Although May claims in this memoir that Charlie suggested to her that “In America they have no idea what a tango is” (20), still, Charlie had found a graceful partner for his avocation in Georgia Hale, his leading lady in The Gold Rush. Her first experience with Charlie outside the studio occurred in the company of soon-to-be-director Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast at the dining room of the Grant Hotel in Los Angeles, just after The Gold Rush had wrapped production. Her account of it in Charlie Chaplin: Intimate Close-ups (1995) is both poignant and telling:

“His favourite dance was the tango. He requested the band to play . . . “La Cumparsita.” Not even Valentino could have out-danced Mr. Chaplin this evening. He was inspired and danced like a native Argentine performer. His contra-shoulder movements made his Gaucho steps dramatic. He bent his knees and straightened them, making the exhibition sensuous and cleverly punctuated. It was thrilling and yet he was so easy to follow, so subtle and firm was his ‘lead.’” (92)

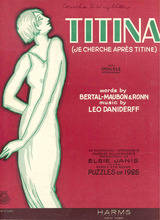

But as with most things Chaplin, this isn’t the whole story. Charlie’s interest and expertise in the tango was reflected back to him in an unusual way. At the height of the initial tango craze in North America in the 1920s, tangos with Little Tramp themes were coming out of Argentina. The two examples of sheet music I have of these tangos are elaborately adorned with folk art renditions of the Little Tramp in one of his film manifestations—as he is in A Dog’s Life (1918) for the tango “La Perra de Chaplin” (the female dog of Chaplin) and as he is in The Idle Class for the tango “El Atorrante* (Carlitos)” (the tramp [Charlie]). Perhaps if Charlie knew about these particular tangos and their attendant Little Tramp art, it would have solidified his passion for the dance even more. Who knows? But actually, the fact that as the overused phrase tells us, “it takes two to tango” is more interesting to think about in terms of Charlie Chaplin, a reputed lone and often irascible figure off-camera and a lone and alienated one on, who shows in this choice of preferred dance-step evidence that contradicts both of these characterizations once again.

*Note that “el Atorrante” is specifically an Argentine word.