Chaplin and the Légion d'Honneur

An article by Lisa Stein Haven

Due to his position as a celebrity and film artist, Chaplin was no stranger to public scrutiny and critique. Early in his career, he was castigated for not serving in World War I and then for a troubled marriage or two. And then there was the issue of taxpaying that seemed to plague him throughout his life in America. These are not the only areas of public critique, but are perhaps the most well known. Lesser-known and/or summarily forgotten is the controversy Chaplin endured in order to be decorated by the French government. His goal was always to receive the highly-regarded Légion d’Honneur medal, equivalent to an English knighthood, but his acquisition of this medal and its attendant respect and honor took nearly ten years and probably ten times the difficulty it needed to. Chaplin received the medal on March 27, 1931.

The story must begin, really, with Chaplin’s first trip back to Europe in September/October 1921. While most of his focus on this trip was on London and his first homecoming there since moving to America to work in films, Chaplin and his party made three trips to Paris as part of the itinerary. Certainly, meeting the French public who greeted him as “Charlot” for the first time, was an important part of these visits, but also there seemed to be a sort of promise to Chaplin that he would be “decorated,” whatever that term happened to mean at the time. On the third trip to Paris, ostensibly to attend the French premiere of The Kid at the Trocadero, “it” happened, but the decoration was for something called “Officier de l’Instruction Publique”—an award given to public school teachers in France. After all this effort, Chaplin still didn’t receive the award he was after and returned to the States empty-handed, although his account of it in My Trip Abroad reveals none of this disappointment:

“Mary [Pickford] and Doug [Fairbanks] are very kind in congratulating me, and I tell them of my terrible conduct during the presentation of the decoration. I knew I was wholly inadequate for the occasion. […] Then they wanted to see the decoration, which reminded me that I had not looked at it myself. So I unrolled the parchment and Doug read aloud the magic words from the Minister of Instruction of the Public and Beaux Arts which made Charles Chaplin, dramatist artist, an Officier de l’Instruction Publique.”

The award he was after—the Cross of the Legion of Honor—is still in existence. Its official website offers this account of the award and its order’s history:

The new order, due to the initiative of the First Consul Bonaparte, consisted of an elite cohort combining the courage of servicemen and talents of civilians, which was to form the basis of a new society to serve the Nation.

On 14 floréal year X (May 4, 1802), Bonapart declared to the Council of State: “If we distinguished men, whether military or civilians, we could establish two Orders while there would only be one Nation. If we were to bestow honors to servicemen only, this preference would be worse as the Nation would no longer be a Nation.”

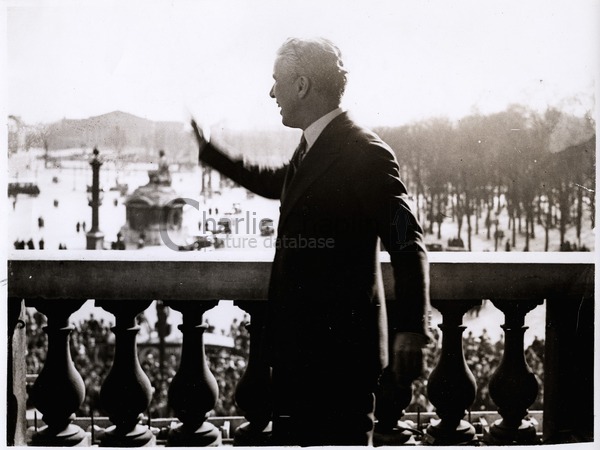

Fast forward ten years to Chaplin’s next tour of Europe, 1931/2. Chaplin and his entourage cut short his trip to Venice in order to be decorated—THE DECORATION this time– in Paris on March 27th and which this time had been secured by the devoted French caricaturist Cami and his friends. Desiring either to avoid any more controversy or simply to show his humility, Chaplin mentions the event in his travel memoir “A Comedian Sees the World” only very briefly: “M. Berthelot, the Permanent Secretary of the French Cabinet, was there [at the luncheon given in Chaplin’s honor at the French Ministry Building] also. He was the gentleman who afterward decorated me” (Part II). The press, however, were less hesitant to discuss the event. In the Seattle Post-Intel’s “Charlie Chaplin’s Troublesome Legion of Honor Medal,” dated July 26, 1931 (news traveled slowly in the days before the Internet), the reporter notes that “the conferring of the rank of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor upon Charlie Chaplin threatens to put an end to all similar honors by wiping out this order, which was founded by Napoleon Bonaparte.” While other headlines echoed the sentiments of “Why Should the Red Ribbon Tinged with Blood of Heroes Be Bestowed on a Clown?” the Post-Intel reporter states that “far from being in any manner unworthy, he is probably the most worthy to receive the decoration in a long time, but he received it just as France was boiling with indignation for what had gone before and what was expected to come.” Other more questionable recipients included a lady inventor of French cheese, the distinguished cook M. Escoffier, and Madame Cecile Sorel, an actress. To make matters worse for Chaplin, African American cabaret singer/dancer Josephine Baker was spreading the rumor at the time (later completely true) that M. Berthelot had promised to bestow the same honor on her in a short time. Would there be no end to this heresy?

Perhaps as interesting (or more interesting) as the scandal surrounding his receipt of the medal is Chaplin’s own apparent heartfelt satisfaction in receiving it. James Abbe, the gifted photographer of celebrities (his wonderful publicity stills for The Pilgrim are perhaps his most famous Chaplin images), offers us an important glimpse into this aspect of the story. Abbe had been camped out near Chaplin’s rooms at the Hotel Crillon for several weeks, hoping for the opportunity to shoot Chaplin’s picture. Being in the right place at the right time, Abbe not only witnessed the first moments after Chaplin’s receipt of the medal, but also recorded these moments both in print and on the celluloid. In a New York Times Herald Tribune article dated April 26, 1931 entitled “Photographing Charlie,” Abbe relates that

“Charlie called us over to the window, naively produced a little leather case from his pocket and opened it to show us the gorgeous Cross of the Legion of Honor, which is ‘le plus beau geste’ which the French can make to an individual. Turning to me Charlie was almost blushing, ‘They say it is the first time it has been given to a foreign actor.’ […] Turning the cross over in his hand, as if it were a sacred relic, he noticed that it did not have his name engraved. For a second we were all three [Abbe, Charlie and Kono], crestfallen. Then Charlie suddenly bethought him of a mailing tube which he had under his arm. […] Then we all bucked up. For there it was in black and white—that Charlie Chaplin was a ‘Chevalier du Légion d’Honneur.’ […] For the first time since I have known him, I saw Charlie, himself, in the same light as his screen personality. His expression and his ever-so-slight pantomime as he showed his valet and me his Cross of the Legion of Honor was identical with that of the little vagabond of the screen, who was so touched by the friendliness of the blind flower girl.”

It’s unfortunate for Chaplin that such a moment had to be so short-lived. Despite the controversy surrounding his decoration, however, I’m sure any amount of negative press at such an event seemed negligible compared to Britain’s handling of Chaplin’s consideration for knighthood—an honor he was supposed to receive on the same tour, but received instead some 44 years later in 1975. How must Charlie have felt, even on the voyage over to Britain on the Mauretania, knowing that his fellow passenger, land speed record holder Malcolm Campbell (yes, a race-car driver), was to receive his knighthood practically upon his landing in Southampton, when he himself was surely to be denied the same honor?